3 Chapter 3: Identity, Culture and Communication

Introduction

3.1 Culture and Communication

Defining Culture

Culture is a complicated word to define, as there are at least six common ways that culture is used in the United States. For the purposes of exploring the communicative aspects of culture, we will define culture as the ongoing negotiation of learned and patterned beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors. Unpacking the definition, we can see that culture should not be conceptualized as stable and unchanging. Culture is “negotiated.” It is also dynamic, and cultural changes can be traced and analyzed to better understand why our society is the way it is. The definition also points out that culture is learned, which accounts for the importance of socializing institutions like family, school, peers, and the media. Culture is patterned in that there are recognizable widespread similarities among people within a cultural group. There is also deviation from and resistance to those patterns by individuals and subgroups within a culture, which is why cultural patterns change over time. Last, the definition acknowledges that culture influences our beliefs about what is true and false, our attitudes (including our likes and dislikes), our values regarding what is right and wrong, and our behaviors. These cultural influences affect our identity and communication.

When people hear the word culture, they often think first of nationality, ethnicity, or race. While these are important and visible aspects of culture (that we will discuss below), they represent only part of the picture. Culture extends far beyond national or ethnic identity and can include elements such as gender, religion, socioeconomic class, generation, region, sexual orientation, and even professional or organizational affiliations. Each of these cultural influences can shape how we view the world, how we communicate, and how we see ourselves and others. Understanding culture as multidimensional helps us appreciate the diversity within groups and avoid assuming that everyone from a particular country or ethnicity shares the same experiences or perspectives.

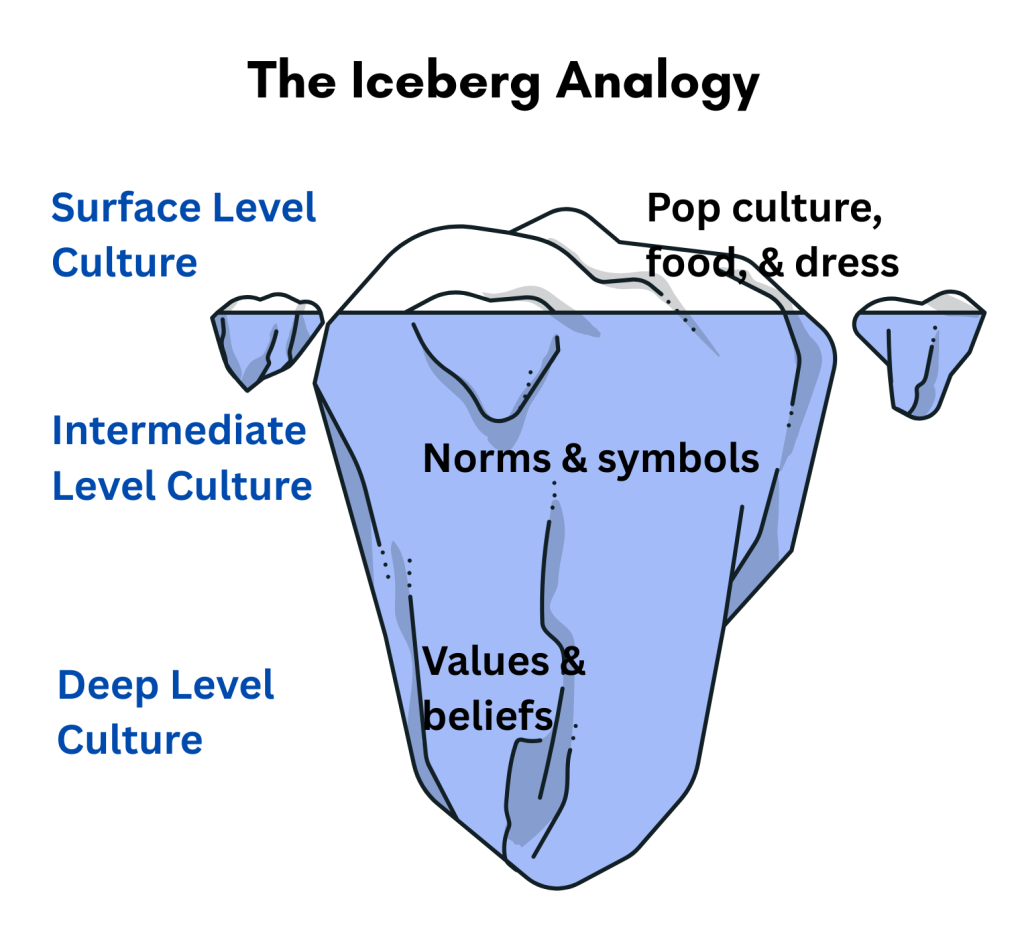

To better understand the complexity of culture, scholars often use the iceberg metaphor. Like an iceberg, only a small portion of culture—such as language, clothing, food, and customs—is visible above the surface (see Figure 3.1). These surface-level elements are easy to observe but do not fully capture the depth of culture. Beneath the surface lie intermediate and deep-level elements such as beliefs, values, thought patterns, norms, and communication styles. These deeper components influence our assumptions about the world and how we interact with others, yet they are often unconscious or taken for granted. Just as the largest and most dangerous part of an iceberg is what’s hidden below, it is often the invisible aspects of culture that lead to misunderstandings or conflict if not recognized and explored.

Remember, truly understanding a culture requires recognizing all aspects of the iceberg—not just what’s visible on the surface. In communication, we often rely on surface cues, but it’s our responsibility to look beneath the surface to form deeper understanding and genuine connections.

Differences Matter

Whenever we encounter someone, we notice similarities and differences. While both are important, often the differences are highlighted. These differences can contribute to communication challenges, especially when we interpret others through the lens of group-based assumptions rather than individual experiences. We tend to place people into in-groups and out-groups based on perceived characteristics, which can lead us to react to someone as a representative of a group rather than as a unique individual (Allen, 2011). In these moments, stereotypes and prejudices are more likely to influence our communication. Learning about difference—and why it matters—is a crucial step toward becoming more effective, respectful communicators.

Some may respond to conversations about difference by saying, “I just see everyone as human.” While this sentiment often comes from a place of good intention, it can overlook the real and lasting effects of identity on people’s lives. Our social and cultural identities—such as race, gender, class, ability, and sexual orientation—shape how we are perceived and how we experience the world (Ting-Toomey & Chung, 2020). Ignoring these aspects of identity can lead to misunderstandings or assumptions that everyone’s experiences are the same. To communicate effectively, we must acknowledge the significance of identity and difference, and recognize that people’s lived experiences can vary widely depending on how they are perceived and treated in society.

Culture and identity are complex and ever-evolving. The meanings attached to different identities change over time and across contexts. These differences are not inherent or fixed, but are shaped by social, political, and historical influences. Understanding how and why certain identities have been emphasized, privileged, or marginalized can help us navigate communication more thoughtfully. Acknowledging this complexity is not about blame—it’s about awareness and growth. Recognizing that not everyone starts from the same place or is treated the same way allows us to build stronger, more empathetic relationships.

Changing demographics also play a role in why difference matters. In the United States, the population is becoming increasingly diverse in terms of many of the sociocultural identities discussed in this chapter. Visibility has grown for people of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, and people with disabilities. For instance, the Hispanic and Latinx population grew by 43 percent from 2000 to 2010 (Saenz, 2011), and by 2030, racial and ethnic minorities are projected to make up one-third of the U.S. population (Allen, 2011). Legal and cultural shifts have also increased representation and advocacy for many historically underrepresented groups. These changes affect our personal, academic, and professional relationships, making cultural awareness and communication skills more essential than ever.

In workplaces and schools, people from different backgrounds are interacting more frequently. While many organizations adopt inclusive policies to comply with laws, others go further to foster environments where diversity is seen as a strength. These inclusive efforts can enhance collaboration, innovation, and morale. But inclusion also requires individuals to reflect on how their own perspectives may differ from others’ and to communicate in ways that are respectful and open-minded.

Unfortunately, there are still obstacles to valuing difference. People who hold dominant identities may struggle to understand the experiences of others simply because they have not faced the same challenges. This lack of awareness can lead to misunderstandings or invalidation of others’ perspectives. At the same time, individuals in non-dominant groups may feel hesitant to speak up due to past negative experiences or fears of being dismissed. Conversations about identity and difference can feel uncomfortable, especially in a culture where political correctness and fear of saying the wrong thing can silence honest dialogue. Yet avoiding these conversations altogether can lead to even greater misunderstandings. By developing intercultural communication competence, we can learn how to navigate these conversations with empathy, curiosity, and a commitment to growth.

3.2 Culture and Identity

Personal, Social, and Cultural Identities

In chapter 2 you were asked to reflect on the question, “who are you?” as we defined the concept of self-concept. In chapter 2 we noted that our sense of self is based on a combination of individual and group factors, as well as what is reflected back on us from other people. Our parents, friends, teachers, and the media help shape our identities. While this happens from birth, most people in Western societies reach a stage in adolescence where maturing cognitive abilities and increased social awareness lead them to begin to reflect on who they are. This begins a lifelong process of thinking about who we are now, who we were before, and who we will become (Tatum, 2000). Our identities make up an important part of our self-concept and can be broken down into three main categories: personal, social, and cultural identities.

Personal identities include the components of self that are primarily intrapersonal and connected to our life experiences (Spreckels & Kotthoff, 2009). Our social identities are the components of self that are derived from involvement in social groups with which we are interpersonally committed. For example, your personal identity may include traits like being creative, ambitious, or introverted—qualities shaped by your unique experiences and reflections. In contrast, your social identity may include being a college student, an athlete, a parent, or a member of a religious, cultural, or linguistic community. These identities often intersect and influence how we see ourselves and how others perceive and communicate with us.

Cultural identities are a type of social identity, that includes “the emotional significance that we attach to our sense of belonging or affiliation with the larger culture and internalization of the core value patterns and practices” (Ting-Toomey & Chung, 2020, p. 95). Some of the larger social and societal groups we belong to – such as our religious affiliation, country or place of birth, ethnic groups – have been influencing our beliefs and behavior systems since birth. We may literally have a parent or leader tell us what it means to be a “man” or a “woman” or a “good Christian”. We may also unconsciously consume messages from popular culture that offer representations of gender or religion. Since we are often a part of them since birth, cultural identities are the least changeable of the three.

We can get a better understanding of current cultural identities by unpacking how they came to be. By looking at history, we can see how cultural identities that seem to have existed forever actually came to be constructed for various political and social reasons and how they have changed over time. Communication plays a central role in this construction. Social constructionism is a view that argues the self is formed through our interactions with others and in relationship to social, cultural, and political contexts (Allen, 2011). In this section, we will explore how the cultural identities of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and ability have been constructed in the United States and how communication relates to those identities. Other important identities could be discussed, like religion, age, nationality, and class. Although they are not given their own section, consider how those identities may intersect with the identities discussed next.

Race and Ethnicity

Would it surprise you to know that all humans, regardless of how they are racially categorized, share 99.9% of the same DNA? This finding from the Human Genome Project demonstrates that race has no meaningful biological basis. Instead, race is a social construct—something created and sustained by society over time to serve particular functions. The American Anthropological Association supports this view, stating that race is “the product of historical and contemporary social, economic, educational, and political circumstances” (Allen, 2011). For our purposes, we will define race as a socially constructed category based on differences in appearance that has been used to create hierarchies that privilege some and disadvantage others.

The concept of race as a meaningful social distinction began during European colonial expansion in the 1500s. As Europeans encountered people in Africa, Asia, and the Americas, they constructed racial categories to justify their actions—particularly conquest, enslavement, and resource extraction. Emerging fields like biology and anthropology at the time attempted to “classify” humans, and some scientists argued that darker-skinned people were less evolved or even subhuman. These pseudo-scientific claims were not only incorrect but also deeply biased, serving to legitimize colonial violence and systemic oppression (Kendi, 2019). Over centuries, race became institutionalized in ways that continue to shape laws, policies, and everyday interactions—even though the science behind racial categories has been thoroughly debunked.

Although race is not biological, it continues to have very real consequences in people’s lives. Because race is one of the first characteristics we perceive about others, it strongly influences social perceptions and communication. Discussions about race can be uncomfortable, often due to fears of saying the wrong thing or using an outdated label. However, avoiding these conversations can contribute to misunderstanding and inequality. Gaining a historical and communicative understanding of race helps us engage more openly, respectfully, and effectively with people from diverse backgrounds.

In the United States, government institutions like the U.S. Census have long played a role in shaping racial categories (see links below). In fact, there have been 26 different racial classifications used on census forms throughout the 1900s alone (Allen, 2011). Currently, the five primary racial groups recognized by the U.S. government are African American, Asian American, European American (White), Latino/a or Hispanic, and Native American. These categories, while still used for broad demographic analysis, are imprecise and often group together individuals with vastly different cultural backgrounds.

- Link to the U.S. Census Historical Look at Race

- Link to the U.S. Census Explanation of Race

- Link to the U.S. Census (2020) break down of racial and ethnic groups in the U.S.

For instance, two individuals may both check the “Asian” box on a demographic form—one might be a first-generation Indian American born in the U.S., and another might be a Chinese immigrant who came to the country in adulthood. Despite being grouped under the same racial label, their cultural practices, languages, religious traditions, and communication norms can differ significantly. This is where the concept of ethnicity becomes useful.

Unlike race, ethnicity refers to shared cultural traits, such as language, religion, national origin, customs, or ancestry. While race is often imposed based on appearance, ethnicity tends to be more self-identified and tied to cultural heritage. For example, someone might identify as Mexican American or Korean American to highlight their ethnic background and cultural identity. Recognizing ethnic diversity within racial categories prevents harmful generalizations and opens up opportunities for deeper understanding.

Table 3.1. Comparison of Race and Ethnicity in Communication

| Category | Race | Ethnicity |

| Definition | A socially constructed category based on physical traits (e.g., skin color, facial features). | A group identity based on shared cultural traits such as language, ancestry, traditions, and religion. |

| Examples | Black, White, Asian, Native American. | Hispanic, Bengali, Mexican, Punjabi, Arab. |

| Number of Categories | Limited and often imposed (e.g., U.S. Census categories). | Potentially limitless, reflecting rich and varied cultural diversity. (For example, there are over 50 ethnic groups within the Asian American population, API-GBV, 2019.) |

| Visibility | Often highly visible and can impact how a person is treated or perceived. | May not be immediately visible and often requires personal disclosure to be understood. |

| Impact on Communication | Influences perception, bias, and experiences of privilege or discrimination. | Shapes language, customs, values, and communicative norms within cultural groups. |

The table above summarizes some distinctions between race and ethnicity that can be essential for improving intercultural communication. Racial identities—especially for people of color—can influence everything from job prospects to interpersonal relationships. At the same time, making assumptions based on race alone can lead to misunderstandings or perpetuate stereotypes. That’s why it’s important to let people define their own identities and to remain open to the complexity of their lived experiences.

Being able to talk about race respectfully and thoughtfully is an important skill in today’s diverse society. While these conversations can be difficult, they are necessary. It’s okay to be uncertain about what terms to use or how to approach a topic—what matters most is the willingness to learn, to listen, and to acknowledge the social realities that shape people’s lives. Avoiding these discussions because of discomfort or fear of being “politically incorrect” only limits opportunities for growth and connection.

Finally, it’s worth emphasizing that having or not having a racial or ethnic identity is part of everyone’s experience, and one is not more valid than the other. What’s important in intercultural communication is an awareness of the historical, cultural, and social forces that influence people’s identities. We can’t assume sameness where there is meaningful difference, nor should we stereotype difference where there may be shared values. By approaching each interaction with curiosity and respect—and letting people speak for themselves—we foster more inclusive, thoughtful communication.

Race and Communication

Race and communication are related in various ways. Racism influences our communication about race and is not an easy topic for most people to discuss. Today, people tend to view racism as overt acts such as calling someone a derogatory name or discriminating against someone in thought or action. However, there is a difference between racist acts, which we can attach to an individual, and institutional racism, which is not as easily identifiable. It is much easier for people to recognize and decry racist actions than it is to realize that racist patterns and practices go through societal institutions, which means that racism exists and does not have to be committed by any one person. As competent communicators and critical thinkers, we must challenge ourselves to be aware of how racism influences our communication at individual and societal levels.

We tend to make some of our assumptions about people’s race based on how they talk, and often these assumptions are based on stereotypes. Dominant groups tend to define what is correct or incorrect usage of a language, and since language is so closely tied to identity, labeling a group’s use of a language as incorrect or deviant challenges or negates part of their identity (Yancy, 2011). We know there is not only one way to speak English, but there have been movements to identify a standard.

This becomes problematic when we realize that “standard English” refers to a way of speaking English that is based on white, middle-class ideals that do not match up with the experiences of many. When we create a standard for English, we can label anything that deviates from that “nonstandard English.” This reflects a bias, and a preference, for one group’s way of communicating. In general, whether someone speaks standard English themselves or not, they tend to judge negatively people whose speech deviates from the standard.

Another national controversy has revolved around the inclusion of Spanish in common language use, such as Spanish as an option at ATMs, or other automated services, and Spanish language instruction in school for students who do not speak or are learning to speak English. As was noted earlier, the Latino/a population in the United States is growing fast, which has necessitated inclusion of Spanish in many areas of public life. This has also created a backlash, which some scholars argue is tied more to the race of the immigrants than the language they speak and a fear that white America could be engulfed by other languages and cultures (Speicher, 2002). This backlash has led to a revived movement to make English the official language of the United States.

One way minority racial groups may manage this language expectation is through the practice of code switching. Code switching involves changing from one way of speaking to another between or within interactions. Some people of color may engage in code switching when communicating with dominant group members because they fear they will be negatively judged. Adopting the language practices of the dominant group may minimize perceived differences. This code switching creates a linguistic dual consciousness in which people are able to maintain their linguistic identities with their in-group peers but can still acquire tools and gain access needed to function in dominant society (Yancy, 2011). White people may also feel anxious about communicating with people of color out of fear of being perceived as racist. In other situations, people in dominant groups may spotlight non-dominant members by asking them to comment on or educate others about their race (Allen, 2011).

Microaggressions are another important area of race-related communication to be aware of. These are subtle, often unintentional, forms of discrimination or bias that can appear in everyday conversation (Wing Sue, 2010) —such as assuming someone is not American because of how they look or complimenting a person of color for being “so articulate,” implying that this is unexpected. Microaggressions may seem small or even well-meaning on the surface, but they reflect and reinforce harmful stereotypes and can have a cumulative negative impact on the mental and emotional well-being of marginalized groups. As communicators, we need to be mindful of how our words and assumptions can reinforce racial hierarchies, even when we don’t intend harm.

One example of a microaggression is, “where are you really from?” When asked of a person based on a non dominant race or accent, it sends the [sometimes unintentional] message: you don’t belong here (Stephens College, n.d.).

In classrooms, workplaces, and interpersonal interactions, microaggressions can disrupt trust and reinforce social exclusion. For example, repeatedly asking someone “Where are you really from?” can suggest that they do not belong, even if they were born and raised in the United States. Recognizing and addressing microaggressions is a critical step in becoming more culturally competent and promoting inclusive communication. It requires ongoing self-awareness, humility, and a willingness to listen and learn from the experiences of others.

Gender Identity and Expression

When we first meet a newborn baby, we ask whether it is a boy or a girl. This question illustrates the importance of gender in organizing our social lives and our interpersonal relationships. A Canadian family became aware of the deep emotions people feel about gender and the great discomfort people feel when they cannot determine gender when they announced to the world that they were not going to tell anyone the gender of their baby, aside from the baby’s siblings. Their desire for their child, named Storm, to be able to experience early life without the boundaries and categories of gender brought criticism from many (Davis & James, 2011).

Conversely, many parents consciously or unconsciously “code” their newborns in gendered ways based on our society’s associations of pink clothing and accessories with girls and blue with boys. While it is obvious to most people that colors are not gendered, they take on new meaning when we assign gendered characteristics of masculinity and femininity to them. Just like race, gender is a socially constructed category. While it is true that there are biological differences between who we label male and female, the meaning our society places on those differences is what actually matters in our day-today lives. In addition, the biological differences are interpreted differently around the world, which further shows that although we think gender is a natural, normal, stable way of classifying things, it is actually not. There is a long history of appreciation for people who cross gender lines in Native American and South Central Asian cultures, to name just two.

You may have noticed the use the word gender instead of sex. That is because gender is an identity based on internalized cultural notions of masculinity and femininity that is constructed through communication and interaction. There are two important parts of this definition to unpack. First, we internalize notions of gender based on socializing institutions, which helps us form our gender identity. Then we attempt to construct that gendered identity through our interactions with others, which is our gender expression. Sex – which is now commonly referred to as sex or gender assigned at birth – since it is determined by others external to us, is based on biological characteristics, including external genitalia, internal sex organs, chromosomes, and hormones (Wood, 2005). While the biological characteristics between males and females can be different, our connection to those terms and the meaning that we create and attach to those characteristics makes them significant. Some common gender identity terms you may here include: man, woman, trans, and nonbinary. It is important to allow others to choose the term that’s best for them. Miscommunication and bias are more likely to occur when we (as observers) assign people into gender groups based on rigid binary stereotypes.

- Cisgender is used to describe people in which their gender identity aligns with their sex or gender assigned at birth. For example, if a baby was identified as a female and that baby grows up to be a child/adult identifies as a girl/woman, this person is considered cisgender. Many cisgender individuals do not use this term, because in many societies being cisgender is considered “the norm” or even the only acceptable identity.

- Transgender is an umbrella term for people whose sex identity and/or expression does not match the sex or gender they were assigned by birth. Transgender people may or may not seek medical intervention like surgery or hormone treatments to help match their physiology with their gender identity. The term transgender includes other labels such as transsexual and intersex, among others. Terms like hermaphrodite and she-male are not considered appropriate. As with other groups, it is best to allow someone to self-identify first and then honor their preferred label. If you are unsure of which pronouns to use when addressing someone, you can use gender-neutral language or you can use the pronoun that matches with how they are presenting.

Gender has been constructed over the past few centuries in political and deliberate ways that have tended to favor men in terms of power. Moreover, various academic fields joined in the quest to “prove” there are “natural” differences between men and women. While the “proof” they presented was credible to many at the time, it seems blatantly sexist and inaccurate today. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, scientists who measure skulls, also known as craniometrists, claimed that men were more intelligent than women were because they had larger brains. Leaders in the fast-growing fields of sociology and psychology argued that women were less evolved than men and had more in common with “children and savages” than an adult (white) males (Allen, 2011).

Doctors and other decision makers like politicians also used women’s menstrual cycles as evidence that they were irrational, or hysterical, and therefore could not be trusted to vote, pursue higher education, or be in a leadership position. These are just a few of the many instances of how knowledge was created by seemingly legitimate scientific disciplines that we can now clearly see served to empower men and disempower women. This system is based on the ideology of patriarchy, which is a system of social structures and practices that maintains the values, priorities, and interests of men as a group (Wood, 2005). One of the ways patriarchy is maintained is by its relative invisibility. While women have been the focus of much research on gender differences, males have been largely unexamined. Men have been treated as the “generic” human being to which others are compared. However, that ignores the fact that men have a gender, too. Masculinities studies have challenged that notion by examining how masculinities are performed.

Gender as a cultural identity has implications for many aspects of our lives, including real-world contexts like education and work. Schools are primary grounds for socialization, and the educational experience for males and females is different in many ways from preschool through college. Although not always intentional, schools tend to recreate the hierarchies and inequalities that exist in society. Given that we live in a patriarchal society, there are communicative elements present in school that support this (Allen, 2011). For example, teachers are more likely to call on and pay attention to boys in a classroom, giving them more feedback in the form of criticism, praise, and help. This sends an implicit message that boys are more worthy of attention and valuable than girls are. Teachers are also more likely to lead girls to focus on feelings and appearance and boys to focus on competition and achievement. The focus on appearance for girls can lead to anxieties about body image.

Gender inequalities are also evident in the administrative structure of schools, which puts males in positions of authority more than females. While females make up 75 percent of the educational workforce, only 22 percent of superintendents and 8 percent of high school principals are women. Similar trends exist in colleges and universities, with women only accounting for 26 percent of full professors. These inequalities in schools correspond to larger inequalities in the general workforce. While there are more women in the workforce now than ever before, they still face a glass ceiling, which is a barrier for promotion to upper management. Many of my students have been surprised at the continuing pay gap that exists between men and women. In 2010, women earned about seventy-seven cents to every dollar earned by men (National Committee on Pay Equity, 2021). To put this into perspective, the National Committee on Pay Equity started an event called Equal Pay Day. In 2011, Equal Pay Day was on April 11. This signifies that for a woman to earn the same amount of money a man earned in a year, she would have to work more than three months extra, until April 11, to make up for the difference (National Committee on Pay Equity, 2021).

Sexuality and Sexual Orientation

While race and gender expression are two of the first things we notice about others, sexuality is often something we view as personal and private. Although many people hold a view that a person’s sexuality should be kept private, this is not a reality for our society. One only needs to observe popular culture and media for a short time to see that sexuality permeates much of our public discourse.

Sexuality relates to culture and identity in important ways that extend beyond sexual orientation, just as race is more than the color of one’s skin and gender is more than one’s biological and physiological manifestations of masculinity and femininity. Sexuality is not just physical; it is social in that we communicate with others about sexuality (Allen, 2011). Sexuality is also biological in that it connects to physiological functions that carry significant social and political meaning like puberty, menstruation, and pregnancy. Sexuality connects to public health issues like sexually transmitted infections (STIs), sexual assault, sexual abuse, sexual harassment, and teen pregnancy. Sexuality is at the center of political issues like abortion, sex education, and gay and lesbian rights. While all these contribute to sexuality as a cultural identity, the focus in this section is on sexual orientation.

Sexual orientation refers to a person’s primary physical and emotional sexual attraction and activity. The terms we most often use to categorize sexual orientation are heterosexual (straight), gay, lesbian, bisexual, and queer. Gays, lesbians, and bisexuals are sometimes referred to as sexual minorities. While the term sexual preference has been used previously, sexual orientation is more appropriate, since preference implies a simple choice. Although someone’s preference for a restaurant or actor may change frequently, sexuality is not as simple. The term homosexual can be appropriate in some instances, but it carries with it a clinical and medicalized tone. As you will see in the timeline that follows, the medical community has a recent history of “treating homosexuality” with means that most would view as inhumane today. So many people prefer a term like gay, which was chosen and embraced by gay people, rather than homosexual, which was imposed by a then discriminatory medical system.

The gay and lesbian rights movement became widely recognizable in the United States in the 1950s and continues on today, as evidenced by prominent issues regarding sexual orientation in national news and politics. National and international groups like the Human Rights Campaign advocate for rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) communities. While these communities are often grouped together within one acronym (LGBTQ), they are different. Gays and lesbians constitute the most visible of the groups and receive the most attention and funding. Bisexuals are rarely visible or included in popular cultural discourses or in social and political movements. Transgender issues have received much more attention in recent years, but transgender identity connects to gender more than it does to sexuality. Last, queer is a term used to describe a group that is diverse in terms of identities but usually takes a more activist and at times radical stance that critiques sexual categories. While queer was long considered a derogatory label, and still is by some, the queer activist movement that emerged in the 1980s and early 1990s reclaimed the word and embraced it as a positive. As you can see, there is a diversity of identities among sexual minorities, just as there is variation within races and genders.

As with other cultural identities, notions of sexuality have been socially constructed in different ways throughout human history. Sexual orientation did not come into being as an identity category until the late 1800s. Before that, sexuality was viewed in more physical or spiritual senses that were largely separate from a person’s identity.

Ability and Disability

There is resistance to classifying ability as a cultural identity, because we follow a medical model of disability that places disability as an individual and medical rather than social and cultural issue. While much of what distinguishes able-bodied and cognitively able from disabled is rooted in science, biology, and physiology, there are important sociocultural dimensions. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) defines an individual with a disability as “a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, a person who has a history or record of such an impairment, or a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment” (Allen, 2011). An impairment is defined as “any temporary or permanent loss or abnormality of a body structure or function, whether physiological or psychological” (Allen, 2011).

This definition is important because it notes the social aspect of disability in that people’s life activities are limited and the relational aspect of disability in that the perception of a disability by others can lead someone to be classified as such. Ascribing an identity of disabled to a person can be problematic. If there is a mental or physical impairment, it should be diagnosed by a credentialed expert. If there is not an impairment, then the label of disabled can have negative impacts, as this label carries social and cultural significance. People are tracked into various educational programs based on their physical and cognitive abilities. In addition, there are many cases of people being mistakenly labeled disabled who were treated differently despite their protest of the ascribed label. Students who did not speak English as a first language, for example, were—and perhaps still are—sometimes put into special education classes.

Ability, just as the other cultural identities discussed, has institutionalized privileges and disadvantages associated with it. Ableism is the system of beliefs and practices that produces a physical and mental standard that is projected as normal for a human being and labels deviations from it abnormal, resulting in unequal treatment and access to resources. Ability privilege refers to the unearned advantages that are provided for people who fit the cognitive and physical norms (Allen, 2011). One of the authors attended a workshop about ability privilege led by a man who was visually impaired. He talked about how, unlike other cultural identities that are typically stable over a lifetime, ability fluctuates for most people. We have all experienced times when we are more or less able.

Statistically, people with disabilities make up the largest minority group in the United States, with an estimated 25 percent of people five years or older living with some form of disability (CDC, 2024). Even though we use an image of a wheelchair to indicate disability, disability is more than mobility restrictions. Disability includes a diverse group of people with a wide range of needs (see 2024 table to the right). Some disabilities may be hidden and not easy to see.

People with disabilities have been stigmatized throughout history. In many cultures, disability has been associated with curses, disease, dependence, and helplessness. Disability stigma can play out in a number of ways, including (Houtenville & Boege, 2019):

- Social Avoidance and Exclusion. People with disabilities may be left out of social activities, or they may find that friends become more distant after they develop a disability. People may be hesitant to make eye contact or start a conversation with someone who has a visible disability or may avoid a person with a cognitive disability whom they do not understand (de Boer et al., 2012).

- Stereotyping. People with disabilities may be presumed to be helpless, unable to care for themselves, or unable to make their own decisions. People with one disability, such as a speech impairment, may be presumed to have other disabilities they don’t have, such as an intellectual disability.

- Discrimination. People with disabilities may be denied jobs, housing, or other opportunities due to false assumptions or stereotypes about disabilities. This still occurs today (see Project WHEN for recent examples), despite disability rights laws such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

- Condescension. People with disabilities may be coddled or over-protected due to perceptions of their helplessness.

- Blaming. People may be blamed for their disability, or accused of using their disability to gain unfair benefits. A recent study of physicians even found that health care workers treating people with disabilities can carry biased views that affect their health care access and outcomes (Iezzoni et al., 2021).

- Internalization. People with disabilities may themselves adopt negative beliefs about their disability and feel ashamed or embarrassed about it. As a society, we have only recently begun to discuss mental health as an important social issue, and given individuals and celebrities the space to discuss mental health conditions and struggles.

- Hate Crimes and Violence. People with disabilities may be targeted in hate crimes. According to the National Center for Victims of Crime, people with disabilities are twice as likely to be victims of crime as compared to people without disabilities, including physical or sexual violence (2018).

It’s important to note that an outsider cannot, 1) see all disabilities, and 2) understand the ways in which a person’s disability is impacting their life. Some people may not see their disability as part of their identity or participate in a cultural community around it. Cultural identity is both personal and social—it varies by context and individual.

3.3 Intercultural Communication Competence

It is through intercultural communication that we come to create, understand, and transform culture and identity. Intercultural communication is communication between people with differing cultural identities. One reason we should study intercultural communication is to foster greater self-awareness (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). Our thought process regarding culture is often “other focused,” meaning that the culture of the other person or group is what stands out in our perception. However, the old adage “know thyself” is appropriate, as we become more aware of our own culture by better understanding other cultures and perspectives. Intercultural communication can allow us to step outside of our comfortable, usual frame of reference and see our culture through a different lens. Additionally, as we become more self-aware, we may also become more ethical communicators as we challenge our ethnocentrism, or our tendency to view our own culture as superior to other cultures.

Intercultural communication competence (ICC) is the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in various cultural contexts. There are numerous components of ICC. Some key components include motivation, self- and other knowledge, and tolerance for uncertainty.

Initially, a person’s motivation for communicating with people from other cultures must be considered. Motivation refers to the root of a person’s desire to foster intercultural relationships and can be intrinsic or extrinsic (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). Put simply, if a person is not motivated to communicate with people from different cultures, then the components of ICC discussed next do not really matter. If a person has a healthy curiosity that drives him or her toward intercultural encounters in order to learn more about self and others, then there is a foundation from which to build additional competence-relevant attitudes and skills. This intrinsic motivation makes intercultural communication a voluntary, rewarding, and lifelong learning process. Motivation can also be extrinsic, meaning that the desire for intercultural communication is driven by an outside reward like money, power, or recognition. While both types of motivation can contribute to ICC, context may further enhance or impede a person’s motivation to communicate across cultures.

Members of dominant groups are often less motivated, intrinsically and extrinsically, toward intercultural communication than members of non-dominant groups, because they do not see the incentives for doing so. Having more power in communication encounters can create an unbalanced situation where the individual from the non-dominant group is expected to exhibit competence, or the ability to adapt to the communication behaviors and attitudes of the other. Even in situations where extrinsic rewards like securing an overseas business investment are at stake, it is likely that the foreign investor is much more accustomed to adapting to United States business customs and communication than vice versa. This expectation that others will adapt to our communication can be unconscious, but later ICC skills we will learn will help bring it to awareness.

The unbalanced situation just described is a daily reality for many individuals with non-dominant identities. Their motivation toward intercultural communication may be driven by survival in terms of functioning effectively in dominant contexts. Recall the phenomenon known as code switching discussed earlier, in which individuals from non-dominant groups adapt their communication to fit in with the dominant group. In such instances, African Americans may “talk white” by conforming to what is called “standard English,” women in corporate environments may adapt masculine communication patterns, people who are gay or lesbian may self-censor and avoid discussing their same-gender partners with coworkers, and people with nonvisible disabilities may not disclose them in order to avoid judgment.

While intrinsic motivation captures an idealistic view of intercultural communication as rewarding in its own right, many contexts create extrinsic motivation. In either case, there is a risk that an individual’s motivation can still lead to incompetent communication. For example, it would be exploitative for an extrinsically motivated person to pursue intercultural communication solely for an external reward and then abandon the intercultural relationship once the reward is attained. These situations highlight the relational aspect of ICC, meaning that the motivation of all parties should be considered. Motivation alone cannot create ICC.

Knowledge supplements motivation and is an important part of building ICC. Knowledge includes self- and other-awareness, mindfulness, and cognitive flexibility. Building knowledge of our own cultures, identities, and communication patterns takes more than passive experience (Martin & Nakayama). Developing cultural self-awareness often requires us to get out of our comfort zones. Listening to people who are different from us is a key component of developing self-knowledge. This may be uncomfortable, because we may realize that people think of our identities differently than we thought.

The most effective way to develop other-knowledge is by direct and thoughtful encounters with other cultures. However, people may not readily have these opportunities for a variety of reasons. Despite the overall diversity in the United States, many people still only interact with people who are similar to them. Even in a racially diverse educational setting, for example, people often group off with people of their own race. While a heterosexual person may have a gay or lesbian friend or relative, they likely spend most of their time with other heterosexuals. Unless you interact with people with disabilities as part of your job or have a person with a disability in your friend or family group, you likely spend most of your time interacting with able-bodied people. Living in a rural area may limit your ability to interact with a range of cultures, and most people do not travel internationally regularly. Because of this, we may have to make a determined effort to interact with other cultures or rely on educational sources like college classes, books, or documentaries. Learning another language is also a good way to learn about a culture, because you can then read the news or watch movies in the native language, which can offer insights that are lost in translation. It is important to note though that we must evaluate the credibility of the source of our knowledge, whether it is a book, person, or other source. In addition, knowledge of another language does not automatically equate to ICC.

Developing self- and other-knowledge is an ongoing process that will continue to adapt and grow as we encounter new experiences. Mindfulness and cognitive flexibility will help as we continue to build our ICC (Pusch, 2009). Mindfulness is a state of self- and other-monitoring that informs later reflection on communication interactions. As mindful communicators, we should ask questions that focus on the interactive process like “How is our communication going? What are my reactions? What are their reactions?” Being able to adapt our communication in the moment based on our answers to these questions is a skill that comes with a high level of ICC. Reflecting on the communication encounter later to see what can be learned is also a way to build ICC. We should then be able to incorporate what we learned into our communication frameworks, which requires cognitive flexibility. Cognitive flexibility refers to the ability to continually supplement and revise existing knowledge to create new categories rather than forcing new knowledge into old categories. Cognitive flexibility helps prevent our knowledge from becoming stale and also prevents the formation of stereotypes and can help us avoid prejudging an encounter or jumping to conclusions. In summary, to be better intercultural communicators, we should know much about others and ourselves and be able to reflect on and adapt our knowledge as we gain new experiences.

Motivation and knowledge can inform us as we gain new experiences, but how we feel in the moment of intercultural encounters is also important. Tolerance for uncertainty refers to an individual’s attitude about and level of comfort in uncertain situations (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). Some people perform better in uncertain situations than others, and intercultural encounters often bring up uncertainty. Whether communicating with someone of a different gender, race, or nationality, we are often wondering what we should or should not do or say. Situations of uncertainty most often become clearer as they progress, but the anxiety that an individual with a low tolerance for uncertainty feels may lead them to leave the situation or otherwise communicate in a less competent manner. Individuals with a high tolerance for uncertainty may exhibit more patience, waiting on new information to become available or seeking out information, which may then increase the understanding of the situation and lead to a more successful outcome (Pusch, 2009). Individuals who are intrinsically motivated toward intercultural communication may have a higher tolerance for uncertainty, in that their curiosity leads them to engage with others who are different because they find the self- and other-knowledge gained rewarding.

Cultivating Intercultural Communication Competence

How can ICC be built and achieved? This is a key question we will address in this section. Two main ways to build ICC are through experiential learning and reflective practices (Bednarz, 2010). We must first realize that competence is not any one thing. Part of being competent means that you can assess new situations and adapt your existing knowledge to the new contexts. What it means to be competent will vary depending on your physical location, your role (personal, professional, etc.), and your life stage, among other things. Sometimes we will know or be able to figure out what is expected of us in a given situation, but sometimes we may need to act in unexpected ways to meet the needs of a situation. Competence enables us to better cope with the unexpected, adapt to the non-routine, and connect to uncommon frameworks. ICC is less about a list of rules and more about a box of tools.

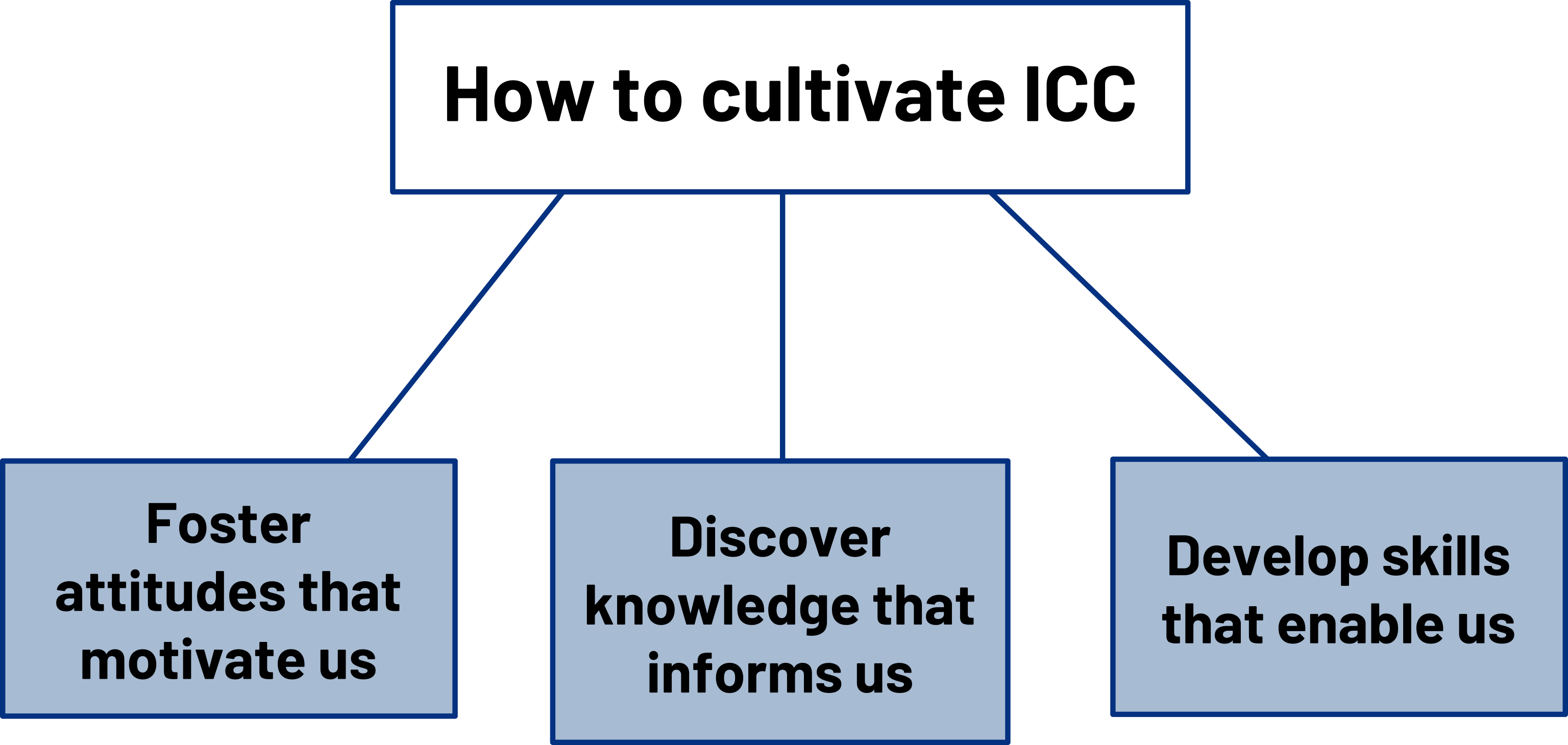

Three ways to cultivate ICC are to 1) foster attitudes that motivate us, 2) discover knowledge that informs us, and 3) develop skills that enable us (Bennett, 2009). To foster attitudes that motivate us, we must develop a sense of wonder about culture. This sense of wonder can lead to feeling overwhelmed, humbled, or awed (Opdal, 2001). This sense of wonder may correlate to a high tolerance for uncertainty, which can help us turn potentially frustrating experiences we have into teachable moments. You may have had such moments in your own experience abroad. For example, trying to cook a pizza when you do not have instructions in your native language. The information on the packaging was written in Swedish, but like many college students, you have a wealth of experience cooking frozen pizzas to draw from. You might think it strange that the oven did not go up to the usual 425–450 degrees. Not to be deterred, and if you cranked the dial up as far as it would go, waited a few minutes, put in your pizza, and walked down the hall to room to wait for about fifteen minutes until the pizza was done. You would soon figure out that the oven temperatures in Sweden are listed in Celsius, not Fahrenheit!

Discovering knowledge that informs us is another step that can build on our motivation. One tool involves learning more about our cognitive style (how we learn). Our cognitive style consists of our preferred patterns for “gathering information, constructing meaning, and organizing and applying knowledge” (Bennett, 2009). As we explore cognitive styles, we discover that there are differences in how people attend to and perceive the world, explain events, organize the world, and use rules of logic (Nisbett, 2003). Some cultures have a cognitive style that focuses more on tasks, analytic and objective thinking, details and precision, inner direction, and independence, while others focus on relationships and people over tasks and things, concrete and metaphorical thinking, and a group consciousness and harmony.

Developing ICC is a complex learning process. At the basic level of learning, we accumulate knowledge and assimilate it into our existing frameworks. However, accumulated knowledge does not necessarily help us in situations where we have to apply that knowledge. Transformative learning takes place at the highest levels and occurs when we encounter situations that challenge our accumulated knowledge and our ability to accommodate that knowledge to manage a real-world situation. The cognitive dissonance that results in these situations is often uncomfortable and can lead to a hesitance to repeat such an engagement. One tip for cultivating ICC that can help manage these challenges is to find a community of like-minded people who are also motivated to develop ICC.

Developing skills that enable us is another part of ICC. Some of the skills important to ICC are the ability to empathize, accumulate cultural information, listen, resolve conflict, and manage anxiety (Bennett, 2009). Again, you are already developing a foundation for these skills by reading this book, but you can expand those skills to intercultural settings with the motivation and knowledge already described. Contact alone does not increase intercultural skills; there must be more deliberate measures taken to capitalize fully on those encounters. While research now shows that intercultural contact does decrease prejudices, this is not enough to become interculturally competent. The ability to empathize and manage anxiety enhances prejudice reduction, and these two skills have been shown to enhance the overall impact of intercultural contact even more than acquiring cultural knowledge. There is intercultural training available for people who are interested. If you cannot access training, you may choose to research intercultural training on your own, as there are many books, articles, and manuals written on the subject.

While formal intercultural experiences like studying abroad or volunteering for the Special Olympics or a shelter for gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer (GLBTQ) youth can result in learning, informal experiences are also important. We may be less likely to include informal experiences in our reflection if we do not see them as legitimate. Reflection should also include “critical incidents” or what I call “a-ha! moments.” Think of reflection as a tool for metacompetence that can be useful in bringing the formal and informal together (Bednarz, 2010).

Wrap Up

Identity, culture and communication are deeply connected, and understanding that connection is a significant step in becoming a more confident and effective communicator. This chapter showed how our personal, social, and cultural identities shape not only how we see the world but also how we communicate with others. You probably noticed that identity isn’t just about nationality or ethnicity — it’s also about the many different groups we belong to and how those identities influence our perspectives and behaviors.

One of the most important takeaways is that intercultural communication competence isn’t something you either have or don’t have. It’s a skill that you develop over time by being curious, open-minded, and willing to learn from your own experiences and from others. You’ve probably already encountered moments where communication didn’t go as planned because of cultural differences — that’s totally normal! What matters is how you reflect on those experiences and use them to grow.

References

Allen, B. J. (2011). Difference matters: Communicating social identity (2nd ed.) Waveland.

Asian Pacific Institute on Gender Based Violence (API-GBV). (2019, May). Asian and Pacific Islander Identities and Diversity. Retrieved from https://api-gbv.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/API-demographics-identities-May-2019.pdf

Bednarz, F. (2010). Building up intercultural competences: Challenges and learning processes. In M. G. Onorati & F. Bednarz (Eds.), Building intercultural competencies: A handbook for professionals in education, social work, and health care (pp. 39-52). Acco.

Bennett, J. M. (2009). Cultivating intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The Sage handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 127-134). Sage.

Carlson, L. (2001). Cognitive ableism and disability studies: Feminist reflections on the history of mental retardation. Hypatia, 16(4), 124-146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2001.tb00756.x

Centers for Disease Control. (2024). Disability Impacts Us All. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html

Collier, M. J. (1996). Communication competence problematics in ethnic friendships. Communication Monographs, 63(4), 314-336. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759609376397

Davis, L., & James, S. D. (2011, May 30). Canadian mother raising her ‘genderless’ baby, Storm, defends her family’s decision. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/canadian-mother-raising-genderless-baby-storm-defends-familys/story?id=52436895

de Boer A., Pijl S. J., Minnaert A. (2012a). Students’ attitudes towards peers with disabilities: a review of the literature. International Journal of Disability & Developmental Education, 59, pp. 379–392. 10.1080/1034912X.2012.723944

Giles, H. (1980). Accommodation theory: Some new directions. York Papers in Linguistics, 9, 30.

Giles, H. (2016). Communication accommodation theory: Negotiating personal relationships and social identities across contexts. Cambridge University Press.

Houtenville, A., & Boege, S. (2019). Annual Report on People with Disabilities in America: 2018. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire, Institute on Disability. Available at https://disabilitycompendium.org/sites/default/files/user-uploads/Annual_Report_2018_Accessible_AdobeReaderFriendly.pdf

Iezzoni, L. I., Rao, S. R., Ressalam, J., Bolcic-Jankovic, D., Agaronnik, N. D., Donelan, K., Lagu, T., & Campbell, E. G. (2021). Physicians’ perceptions of people with disability and their health care. Health Affairs, 40 (2).

Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. Random House.

Martin, J. N., & Nakayama, T. K. (2010). Intercultural communication in contexts (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

National Committee on Pay Equity (2021). Worse than we thought. https://www.pay-equity.org/

National Center for Victims of Crime. (2018). Crimes Against People With Disabilities: Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://ovc.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh226/files/ncvrw2018/info_flyers/fact_sheets/2018NCVRW_VictimsWithDisabilities_508_QC.pdf

Nisbett, R. E. (2003). The geography of thought: How Asians and westerners think differently…and why. Free Press.

Opdal, P. M. (2001). Curiosity, wonder, and education seen as perspective. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 20(4), 331–44. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011851211125

Pusch, M. D. (2009). The interculturally competent global leader. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The Sage handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 66-84). Sage.

Saenz, A. (2011, March 21). Census data shows a changed American landscape. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/census-data-reveals-changed-american-landscape/story?id=13206427

Speicher, B. L. (2002). Problems with English-only policies. Management Communication Quarterly, 15(4), 619-625.

Spreckels, J., & Kotthoff, H. (2009). Communicating identity in intercultural communication. In H. Kotthoff & H. Spencer-Oatey, Handbook of intercultural communication (pp. 415-419). Mouton de Gruyter.

Stephens College. (n.d.). Tool: Recognizing Microaggressions and the Messages They Send. Retrieved from https://www.stephens.edu/files/resources/microaggressions-examples-arial-2014-11-12-suewile.pdf

Tatum, B. D. (2000). The complexity of identity: ‘Who am I?’ In M. Adams, W. J. Blumfeld, R. Casteneda, H. W. Hackman, M. L. Peters, & X. Zuniga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (pp. 9-14). Routledge.

Ting-Toomey, S., & Chung, L. C. (2020). Understanding Intercultural Communication. Oxford University Press.

Wing Sue, D. (2010). Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender and Sexual Orientation. Wiley & Sons.

Wood, J. T. (2005). Gendered lives: Communication, gender, and culture (5th ed.) Thomas Wadsworth.

Yancy, G. (2011). The scholar who coined the term Ebonics: A conversation with Dr. Robert L. Williams. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 10(1), 41–51.

Yep, G. A. (1998). My three cultures: Navigating the multicultural identity landscape. In J. N. Martin, T. K. Nakayama & L. A. Flores (Eds.), Readings in cultural contexts (pp. 79-84). Mayfield.

Zuckerman, M. A. (2010). Constitutional clash: When English-only meets voting rights. Yale Law and Policy Review, 28 (2): 353–377. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27871299

Figures

Figure 3.1: The iceberg analogy. Carolyn Hurley. 2025. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.2: The Hispanic and Latinx population has grown 43% since 2000. Jhon David. 2018. Unsplash license. https://unsplash.com/photos/3WgkTDw7XyE

Figure 3.3: Mug with Rainbow Flags. RDNE Stock Project. 2021. Pexels license. https://www.pexels.com/photo/mug-with-rainbow-flags-10503405/

Figure 3.4: Competent communicators challenge themselves through awareness. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0. Includes Think by Brandon Lim from NounProject (NounProject license).

Figure 3.5: Ability is a social identity that makes up the largest minority group in the U.S.. CDC. 2021. Unsplash license. https://unsplash.com/photos/68zwHPkpxpI

Figure 3.6: Intercultural communication can foster greater self-awareness and more ethical communication. Ivan Samkov. 2021. Pexels license. https://www.pexels.com/photo/coworkers-looking-at-a-laptop-in-an-office-8127690/

Figure 3.7: How to cultivate intercultural communication competence. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0.

This chapter was adapted from Culture and Communication in Communication in the Real Word by Faculty members in the School of Communication Studies, James Madison University, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 license. It has been modified and expanded by the Editor to fit the context of Communication in the Real World, and is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

An ongoing negotiation of learned and patterned beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors

Based on socially constructed categories that teach us a way of being and include expectations for social behavior or ways of acting

A view that argues the self is formed through our interactions with others and in relationship to social, cultural, and political contexts

A socially constructed category based on differences in appearance that has been used to create hierarchies that privilege some and disadvantage others

Involves changing from one way of speaking to another between or within interactions

An identity based on internalized cultural notions of masculinity and femininity that is constructed through communication and interaction

Based on biological characteristics, including external genitalia, internal sex organs, chromosomes, and hormones

Communication between people with differing cultural identities

Our tendency to view our own culture as superior to other cultures

The ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in various cultural contexts. Some key components include motivation, self-and-other knowledge, and tolerance for uncertainty.

A state of self- and other-monitoring that informs later reflection on communication interactions