7 Chapter 7: Building and Maintaining Relationships

Introduction

Over the course of our lives, we enter into—and move on from—a variety of relationships. For many people, close relationships are a key ingredient for a fulfilling life. Research from the Pew Research Center (Goddard, 2023; Goddard & Parker, 2025) highlights several insights into how Americans experience and communicate within these relationships:

-

Most Americans report having between one and four close friends, while 38% say they have five or more.

-

In these friendships, people commonly talk about topics like work, family, current events, physical and mental health, pop culture, and sports.

-

We depend on close relationships—such as those with romantic partners, family members, or friends—for social support.

-

At the same time, younger adults in the U.S. are increasingly reporting feelings of loneliness.

Given how essential communication is to creating and sustaining meaningful relationships, this chapter explores how we use communication to build, maintain, and sometimes even let go of our interpersonal connections.

7.1 The Nature of Relationships

We’ve all experienced a wide range of relationships throughout our lives. But what makes something a relationship? How often do we need to see each other? Do we both have to agree that we’re in a relationship? Is following someone on social media enough to qualify?

To better understand the relationships in our lives, we’ll start by exploring key characteristics that define relationships—and the different types and purposes they serve.

7.1.1 Defining Relationships

A relationship is a “connection established when one person communicates with another” (Beebe, Beebe, & Redmond, 2019). These connections can be built in a variety of contexts—family, work, school, shared hobbies, or common experiences. And they serve different purposes: task-oriented, work-related, or social and emotional.

Relationships can also be understood through the lens of choice. Communication scholars often differentiate between relationships of choice and relationships of circumstance (Beebe, Beebe, & Redmond, 2019):

-

Relationships of circumstance are formed due to factors beyond our control—such as our family members, classmates, coworkers, or in-laws. We didn’t choose these individuals, but circumstances brought us together.

-

Relationships of choice, on the other hand, are relationships we actively seek and maintain, like close friendships, romantic partnerships, or mentors.

This distinction is important because our level of investment, expectations, and communication patterns often differ depending on whether the relationship was chosen or circumstantial.

Consider how you might interact with a sibling versus a best friend, or with a coworker versus a partner. The reasons we enter and sustain these relationships—and how we communicate within them—can vary significantly based on their origin.

Table 1. Examples of Relationships of Choice & Circumstance

| Choice | Circumstance |

| Partners

Spouses Best friends Friends Acquaintances Activity partners |

Parent-child

Siblings Grandparents, Aunts, Uncles, Cousins Distant relatives Coworkers/colleagues Neighbors Classmates Teachers |

7.1.2 Purposes of Relationships

We typically form and maintain relationships for one or more of the following purposes:

-

Work-related relationships help us achieve professional or career goals. These connections often arise in the workplace and may involve collaboration, mentorship, or networking.

-

Task-related relationships exist to accomplish a specific goal. Once the task is complete—such as a school project or athletic season—the relationship may dissolve or evolve into something else.

-

Social relationships provide emotional benefits such as affection, inclusion, and support. These relationships are often built on personal choice and include friends, romantic partners, and sometimes family members.

It’s important to note that relationships can serve multiple purposes. For example, a classmate might start as a task-related partner on a project but later become a close friend. A romantic partner may provide both emotional support and collaboration on life goals.

Where does family fit in?

Family relationships are typically considered relationships of circumstance, but in terms of purpose, they often serve social and emotional functions, like offering affection, a sense of belonging, and life support. At times, family relationships can also be task-oriented, especially when caregiving or shared responsibilities are involved.

Consider your own relationships. Which ones provide emotional support? Which ones help you meet goals or complete tasks? Do some do both? The purpose of a relationship can evolve over time, and understanding the roles they play helps us communicate more effectively within them.

7.1.2 Relationship Characteristics

However, all relationships are not the same. The following relationship characteristics help define and differentiate our relationships with others. These characteristics are: duration, contact frequency, sharing, support, interaction variability, and goals (Gamble & Gamble, 2014).

Some friendships last a lifetime, others last a short period. The length of any relationship is referred to as that relationship’s duration. People who grew up in small towns might have had the same classmate till graduation. This is due to the fact that duration with each person is different. Some people we meet in college and we will never see them again. Hence, our duration with that person is short. Duration is related to the length of your relationship with that person.

Second, contact frequency is how often you communicate with their other person. There are people in our lives we have known for years but only talk to infrequently. The more we communicate with others, the closer our bond becomes to the other person. Sometimes people think duration is the real test of a relationship, but it also depends on how often you communicate with the other person.

The third relationship characteristic is sharing. The more we spend time with other people and interact with them, the more we are likely to share information about ourselves. This type of sharing often involves private, intimate details about our thoughts and feelings. We typically don’t share this information with a stranger. Once we develop a sense of trust and support with this person, we can begin to share more details.

The fourth characteristic is support. Think of the people in your life and who you would be able to call in case of an emergency. The ones that come to mind are the ones you know who would be supportive of you. They would support you if you needed help, money, time, or advice. For instance, if you need relationship advice, you would probably pick someone who has relationship knowledge and would support you in your decision. Support is so important. It was found that a major difference between married and dating couples is that married couples were more likely to provide supportive communication behaviors to their partners more than dating couples (Punyanunt-Carter, 2004).

The fifth defining characteristic of relationships is the interaction variability. When we have a relationship with another person, it is not defined on your interaction with them, rather on the different types of conversations you can have with that person. When you were little, you probably knew that if you were to approach your mom, she might respond a certain way as opposed to your Dad, who might respond differently. Hence, you knew that your interaction would vary. The same thing happens with your classmates because you don’t just talk about class with them. You might talk about other events on campus or social events. Therefore, our interactions with others are defined by the greater variability that we have with one person as opposed to another.

The last relationship characteristic is goals. In every relationship we enter into, we have certain expectations about that relationship. For instance, if your goal is to get closer to another person through communication, you might share your thoughts and feelings and expect the other person to do the same. If they do not, then you will probably feel like the goals in your relationship were not met because they didn’t share information. The same goes for other types of relationships. We typically expect that our significant other will be truthful, supportive, and faithful. If they break that goal, then it causes problems in the relationship and could end the relationship. Hence, in all our relationships, we have goals and expectations about how the relationship will function and operate.

7.2 Relationship Formation

Understanding why we form relationships is only part of the picture. To build meaningful connections, we also need to understand how relationships begin in the first place. Whether it’s a friendship, romantic partnership, or professional connection, certain factors influence who we’re drawn to and why we choose to engage. In this section, we’ll explore the process of relational formation through the lens of interpersonal attraction theory (Duck, 1993; Graziano & Bruce, 2008)—which examines how factors such as proximity, similarity, physical attractiveness, and reciprocal liking may lead to new connections.

7.2.1 Understanding Attraction

Before we build relationships, something must first draw us toward another person. This initial pull is known as interpersonal attraction, the force that brings people together and motivates us to pursue a connection (Duck, 1993). Whether you’re meeting someone in class, online, or through mutual friends, attraction plays a key role in whether we choose to engage further. But attraction isn’t a one-size-fits-all concept—it can take on different forms depending on the context and the individuals involved.

Researchers have identified three primary types of attraction: physical, social, and task. Physical attraction refers to the degree to which you find another person aesthetically pleasing. What is deemed aesthetically pleasing can alter greatly from one culture to the next. We also know that pop culture can greatly define what is considered to be physically appealing from one era to the next. For example, in the U.S. in the 1950s, curvy women like Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor depicted an industry standard of “beauty” , whereas in the 1990s, supermodels who were thin and tall dominated the screens. Although discussions of male physical attraction occur less often, they are equally impacted by pop culture. In the 1950s, you had solid men like Robert Mitchum and Marlon Brando as compared to the heavily muscled men of the 2010s like Joe Manganiello or Zac Efron.

The second type of attraction is social attraction, or the degree to which an individual sees another person as entertaining, intriguing, and fun to be around. We all have finite sources when it comes to the amount of time we have in a given day. We prefer to socialize with people that we think are fun. These people may entertain us or they may just fascinate us. No matter the reason, we find some people more socially desirable than others. Social attraction can also be a factor of power. For example, in situations where there are kids in the “in-group” and those that are not. In this case, those that are considered popular hold more power and are perceived as being more socially desirable to associate with. This relationship becomes problematic when these individuals decide to use this social desirability as a tool or weapon against others.

The final type of attraction is task attraction, or people we are attracted to because they possess specific knowledge and/or skills that help us accomplish specific goals. The first part of this definition requires that the target of task attraction possess specific knowledge and/or skills. Maybe you have a friend who is good with computers who will always fix your computer when something goes wrong. Maybe you have a friend who is good in math and can tutor you. Of course, the purpose of these relationships is to help you accomplish your own goals. In the first case, you have the goal of not having a broken down computer. In the second case, you have the goal of passing math. This is not to say that an individual may only be viewed as task attractive, but many relationships we form are because of task attraction in our lives.

7.2.2 Reasons for Attraction

Now that we’ve looked at the basics of what attraction is. Let’s switch gears and talk about why we are attracted to each other. There are several reasons researchers have found for our attraction to others including proximity, physicality, perceived gain, similarities and differences, and disclosure.

Physical Proximity

When you ask some people how they met their significant other, you will often hear proximity is a factor in how they met. Perhaps, they were taking the same class or their families went to the same grocery store. These commonplaces create opportunities for others to meet and mingle. We are more likely to talk to people that we see frequently.

Physical Attractiveness

In day-to-day interactions, you are more likely to pay attention to someone you find more attractive than others. Research shows that males place more emphasis on physical attractiveness than females (Samovar, & Porter, 1995). Appearance is very important at the beginning of the relationship.

Perceived Gain

When we feel drawn to someone—whether as a friend, romantic partner, or collaborator—one key reason is often the rewards we associate with that person. In the context of interpersonal attraction theory, rewards refer to the positive outcomes or benefits we expect to gain from being around someone.

- Rewards are the things we want to acquire. They could be tangible (e.g., food, money, clothes) or intangible (support, admiration, status).

- Costs are undesirable things that we don’t want to expend a lot of energy to do. For instance, we don’t want to have to constantly nag the other person to call us or spend a lot of time arguing about past items.

According to Social Exchange Theory (see sidebar), we tend to be attracted to people who offer us high rewards with relatively low costs (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). For instance, you might feel drawn to someone because they make you laugh (social reward), boost your confidence (emotional reward), or help you with class assignments (task reward). When we perceive that being in a relationship with someone is likely to be rewarding, that perception increases our attraction to them.

This doesn’t mean attraction is purely transactional—but it does suggest that our minds often evaluate relationships in terms of what we gain or stand to lose, even if we’re not consciously doing the math.

When seeking new relationships, we tend to look for others that can help us or benefit us in some way. This type of relationship might appear to be like an economic model and can be explained by exchange theory (Stafford, 2008). In other words, we will form relationships with people who can offer us rewards that outweigh the costs.

Similarities and Differences

It feels comforting when someone who appears to like the same things you like also has other similarities to you. Thus, you don’t have to explain yourself or give reasons for doing things a certain way. People with similar cultural, ethnic, or religious backgrounds are typically drawn to each other for this reason. It is also known as similarity thesis. The similarity thesis basically states that we are attracted to and tend to form relationships with others who are similar to us (Adler, Rosenfeld, & Proctor II, 2013). There are three reasons why similarity thesis works: validation, predictability, and affiliation.

- First, it is validating to know that someone likes the same things that we do. It confirms and endorses what we believe. In turn, it increases support and affection.

- Second, when we are similar to another person, we can make predictions about what they will like and not like. We can make better estimations and expectations about what the person will do and how they will behave.

- The third reason is due to the fact that we like others that are similar to us and thus they should like us because we are the same. Hence, it creates affiliation or connection with that other person.

However, there are some people who are attracted to someone completely opposite from who they are. This is where differences come into play. Differences can make a relationship stronger, especially when you have a relationship that is complementary. In complementary relationships, each person in the relationship can help satisfy the other person’s needs. For instance, one person likes to talk, and the other person likes to listen. They get along great because they can be comfortable in their communication behaviors and roles. In addition, they don’t have to argue over who will need to talk. Another example might be that one person likes to cook, and the other person likes to eat. This is a great relationship because both people are getting what they like to do, and it complements each other’s talents. Usually, friction will occur when there are differences of opinion or control issues. For example, if you have someone who loves to spend money and the other person who loves to save money, it might be very hard to decide how to handle financial issues.

Disclosure

Sometimes we form relationships with others after we have disclosed something about ourselves to others. Disclosure, or sharing about yourself, increases liking because it creates support and trust between you and this other person. We typically don’t disclose our most intimate thoughts to a stranger. We do this behavior with people we are close to because it creates a bond with the other person.

Disclosure is not the only factor that can lead to forming relationships. Disclosure needs to be appropriate and reciprocal (Dindia, 2000). In other words, if you provide information, it must be mutual. If you reveal too much or too little, it might be regarded as inappropriate and can create tension. Also, if you disclose information too soon or too quickly in the relationship, it can create some negative outcomes.

7.3 Stages of Relationships

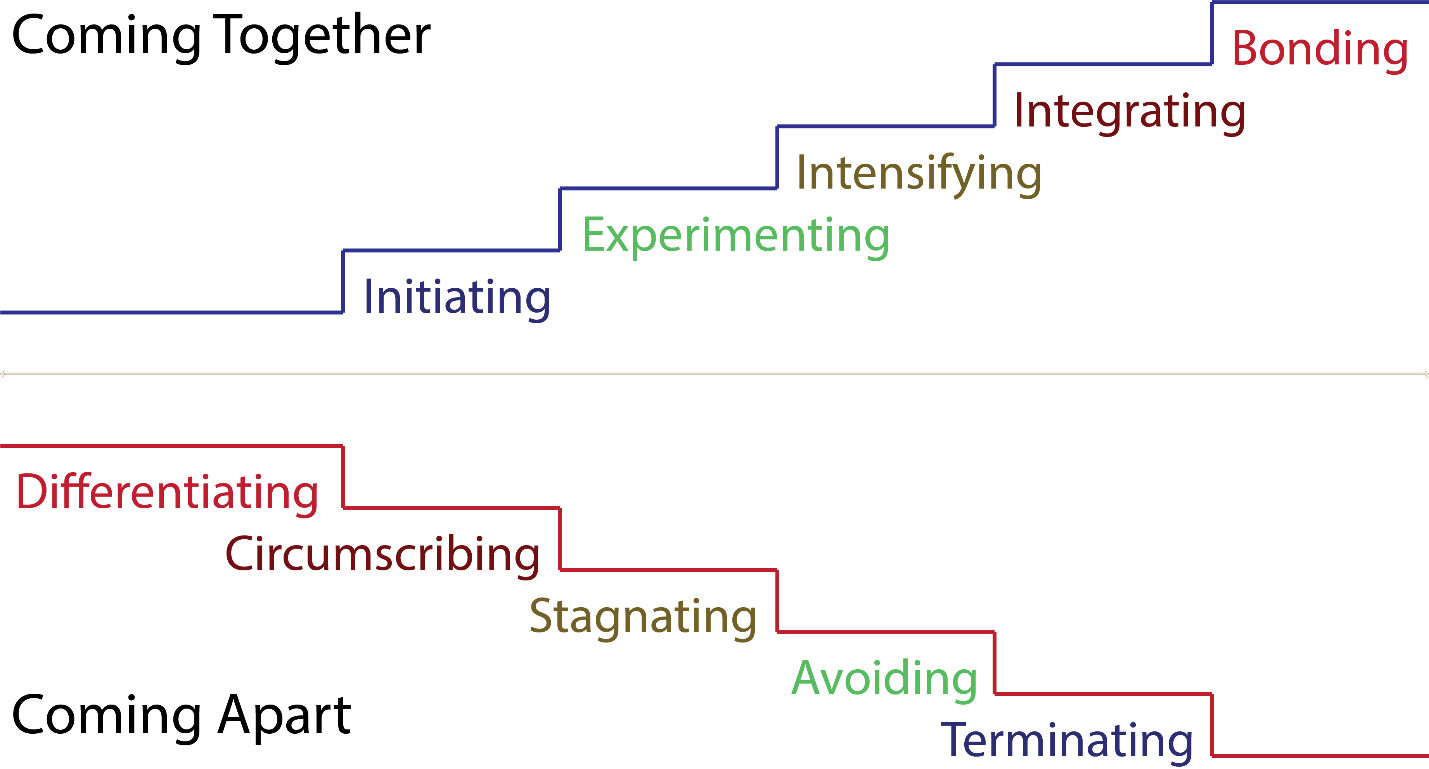

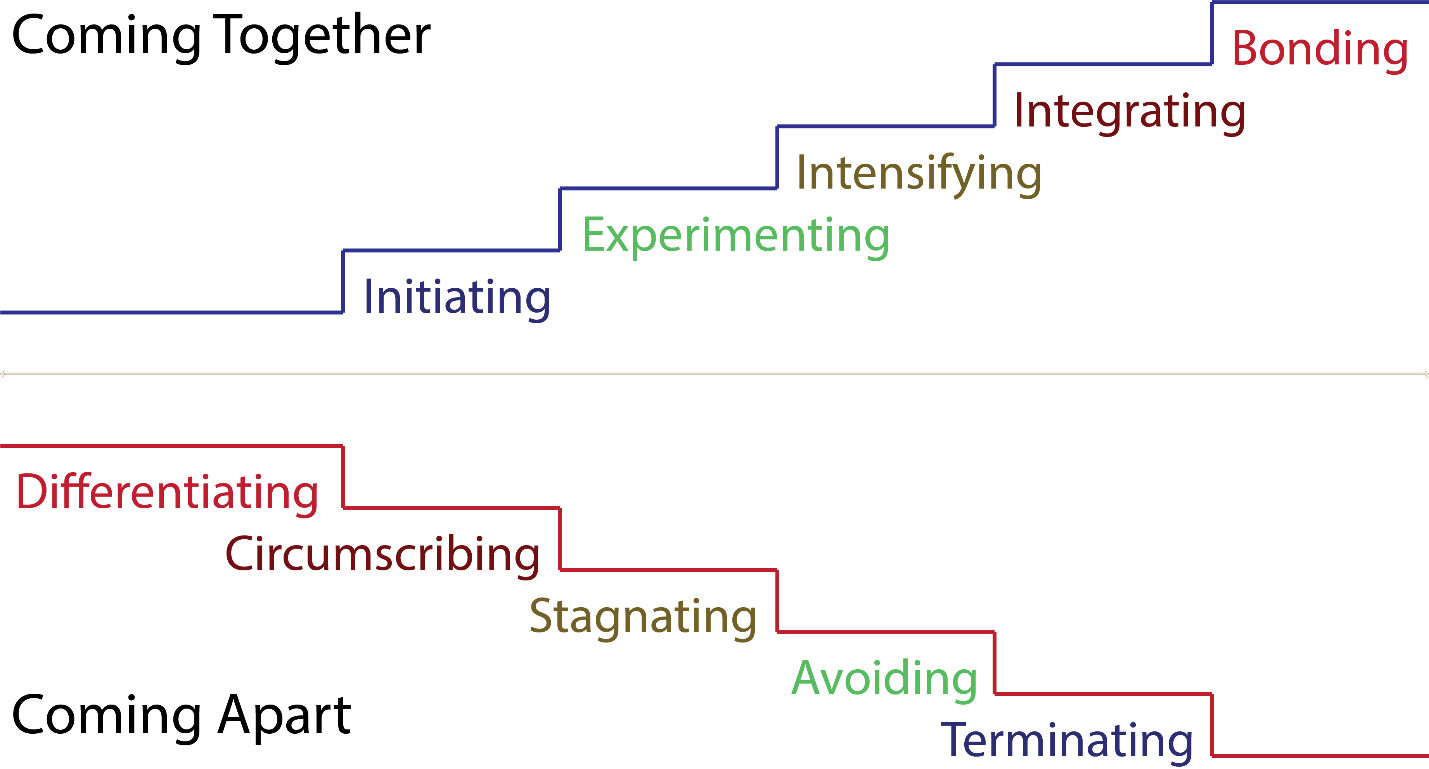

Every relationship goes through various stages. Mark Knapp first introduced The Stage Model of Relationship Development after identifying patterns on the ways many relationships of choice progress (1984; Knapp & Vangelisti, 1992). The following model describes these five stages of coming together, and five stages of coming apart. As you read about the stages, remember that all relationships do not go through ALL stages. You may have only experienced a few relationships that have progressed into a bonding stage. Relationships can also go backwards and forwards through this model. It is normal to experience some de-escalation in a friendship that grows apart, but this can be followed with an escalation period as you and your friend become close again.

7.3.1 Coming Together

Do you remember when you first met that special someone in your life? How did your relationship start? How did you two become closer? Every relationship has to start somewhere. It begins and grows. In this section, we will learn about the coming together stages, which include: initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, and then bonding.

Initiating

At the beginning of every relationship, we have to figure out if we want to put in the energy and effort to talk to the other person. If we are interested in pursuing the relationship, we have to let the other person know that we are interested in initiating a conversation.

There are different types of initiation. Sustaining is trying to continue the conversation. Networking is where you contact others for a relationship. An offering is where you present your interest in some manner. Approaching is where you directly make contact with the other person. We can begin a relationship in a variety of different ways.

Communication at this initiating stage is very brief. We might say hello and introduce yourself to the other person. You might smile or wink to let the other person know you are interested in making conversation with him or her. The conversation is very superficial and not very personal at all. At this stage, we are primarily interested in making contact.

Experimenting

After we have initiated communication with the other person, we go to the next stage, which is experimenting. At this stage, you are trying to figure out if you want to continue the relationship further. We are trying to learn more about the other person.

At this stage, interactions are very casual. You are looking for common ground or similarities that you share. You might talk about your favorite things, such as colors, sports, teachers, etc. Just like the name of the stage, we are experimenting and trying to figure out if we should move towards the next stage or not.

Intensifying

After we talk with the other person and decide that this is someone we want to have a relationship with, we enter the intensifying stage. We share more intimate and/or personal information about ourselves with that person. Conversations become more serious, and our interactions are more meaningful. At this stage, you might stop saying “I” and say “we.” So, in the past, you might have said to your partner, “I am having a night out with my friends.” It changes to “we are going to with my friends tonight.” We are becoming more serious about the relationship.

Integrating

The integrating stage is where two people truly become a couple. Before they might have been dating or enjoying each other’s company, but in this stage, they are letting people know that they are exclusively dating each other. The expectations in the relationship are higher than they were before. Your knowledge of your partner has increased. The amount of time that you spend with each other is greater.

Bonding

The next stage is the bonding stage, where you reveal to the world that your relationship to each other now exists. This only occurs with a few relationships. For example, the bonding stage could be when two partners get engaged and have an engagement announcement. For those that are very committed to the relationship, they might decide to have a wedding and get married. In every case, they are making their relationship a public announcement. They want others to know that their relationship is real.

Not every relationship will go through each of the ten stages. Several relationships do not go past the experimenting stage. Some remain happy at the intensifying or bonding stage. When both people agree that their relationship is satisfying and each person has their needs met, then stabilization occurs. Some relationships go out of order as well. For instance, in some arranged marriages, the bonding occurs first, and then the couple goes through various phases. Some people jump from one stage into another. When partners disagree about what is optimal stabilization, then disagreements and tensions will occur.

In today’s world, romantic relationships can take on a variety of different meanings and expectations. For instance, “hooking up” or having “friends with benefits” are terms that people might use to describe the status of their relationship. Many people might engage in a variety of relationships but not necessarily get married. We know that relationships vary from couple to couple. No matter what the relationship type, couples decided to come together or come apart.

7.3.2 Coming Apart

Some couples can stay in committed and wonderful relationships. However, there are some couples that after bonding, things seem to fall apart. No matter how hard they try to stay together, there is tension and disagreement. These couples go through a coming apart process that involves: differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, and terminating.

Differentiating

The differentiating stage is where both people are trying to figure out their own identities. Thus, instead of trying to say “we,” the partners will question “how am I different?” In this stage, differences are emphasized and similarities are overlooked.

As the partners differentiate themselves from each other, they tend to engage in more disagreements. The couples will tend to change their pronoun use from “our kitchen” becomes “my kitchen” or “our child” becomes “my child,” depending on what they want to emphasize.

Initially, in the relationship, we tend to focus on what we have in common with each other. After we have bonded, we are trying to deal with balancing our independence from the other person. If this cannot be resolved, then tensions will emerge, and it usually signals that your relationship is coming apart.

Circumscribing

The circumscribing stage is where the partners tend to limit their interactions with each other. Communication will lessen in quality and quantity. Partners try to figure out what they can and can’t talk about with each other so that they will not argue.

Partners might not spend as much time with each other at this stage. There are fewer physical displays of affection, as well. Intimacy decreases between the partners. The partners no longer desire to be with each other and only communicate when they have to.

Stagnating

The next stage is stagnating, which means the relationship is not improving or growing. The relationship is motionless or stagnating. Partners do not try to communicate with each other. When communication does occur, it is usually restrained and often awkward. The partners live with each other physically but not emotionally. They tend to distance themselves from the other person. Their enthusiasm for the relationship is gone. What used to be fun and exciting for the couple is now a chore.

Avoiding

The avoiding stage is where both people avoid each other altogether. They would rather stay away from each other than communicate. At this stage, the partners do not want to see each other or speak to each other. Sometimes, the partners will think that they don’t want to be in the relationship any longer.

Terminating

The terminating stage is where the parties decide to end or terminate the relationship. It is never easy to end a relationship. A variety of factors can determine whether to cease or continue the relationship. Time is a factor. Couples have to decide to end it gradually or quickly. Couples also have to determine what happens after the termination of the relationship. Besides, partners have to choose how they want to end the relationship. For instance, some people end the relationship via electronic means (e.g., text message, email, social media posting) or via face-to-face.

7.4 Relationship Maintenance

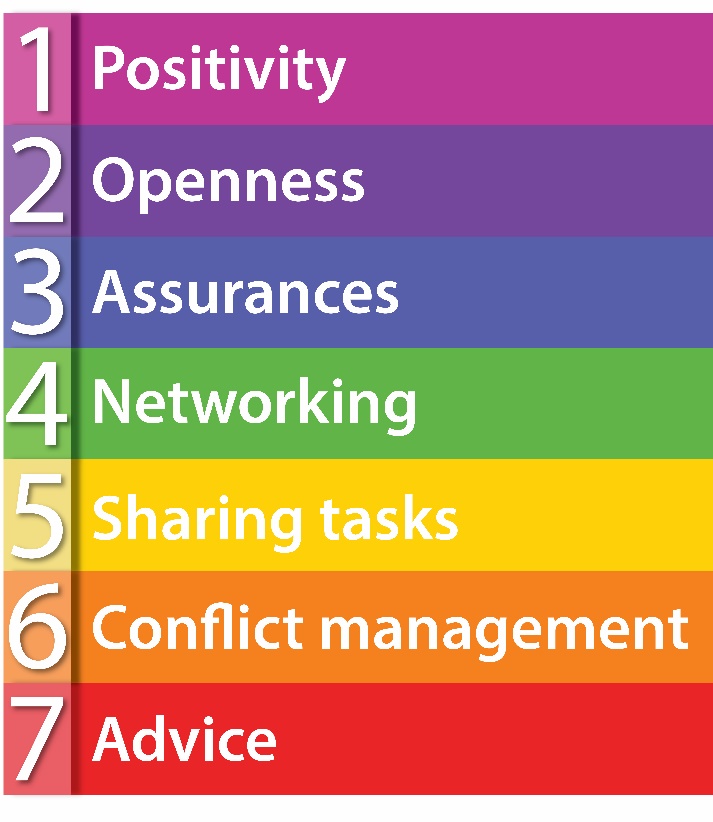

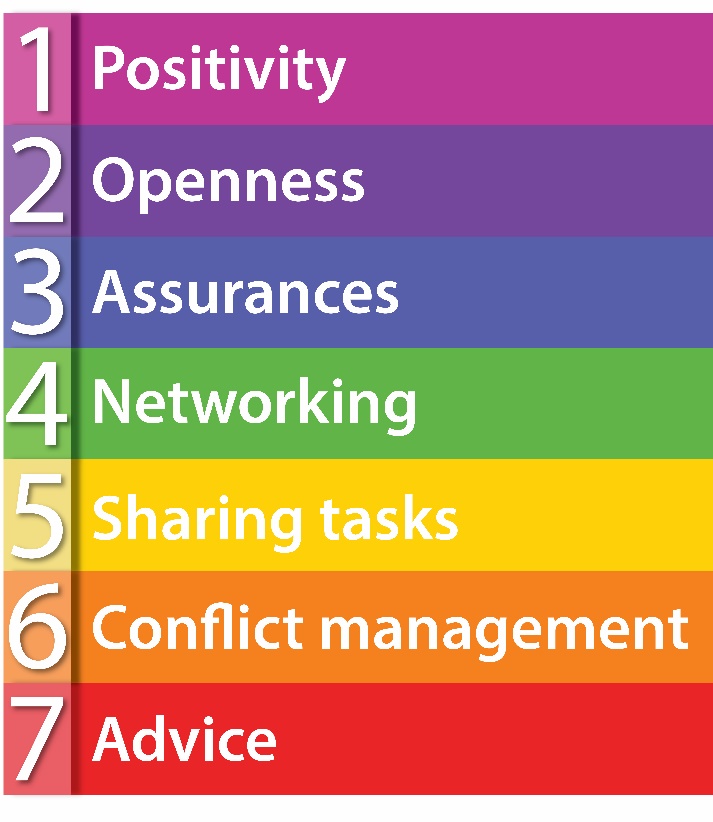

You may have heard that relationships are hard work. Relationships need maintenance and care. Just like your body needs food and your car needs gasoline to run, your relationships need attention as well. When people are in a relationship with each other, what makes a difference to keep people together is how they feel when they are with each other. Maintenance can make a relationship more satisfying and successful.

Daniel Canary and Laura Stafford stated that “most people desire long-term, stable, and satisfying relationships” (1994). To keep a satisfying relationship, individuals must utilize relationship maintenance behaviors. They believed that if individuals do not maintain their relationships, the relationships will weaken and/or end. “It is naïve to assume that relationships simply stay together until they fall apart or that they happen to stay together” (Canary & Stafford, 1994).

Relationship maintenance is the stabilization point between relationship initiation and potential relationship destruction (Duck, 1988). There are two elements to relationship maintenance. First, strategic plans are intentional behaviors and actions used to maintain the relationship. Second, everyday interactions help to sustain the relationship. Most importantly, talk is the most important element in relationship maintenance (Duck, 1994).

Laura Stafford and Daniel Canary (1991) found five key relationship maintenance behaviors.

- First, positivity is a relational maintenance factor used by communicating with their partners in a happy and supportive manner.

- Second, openness occurs when partners focus their communication on the relationship.

- Third, assurances are words that emphasize the partners’ commitment to the duration of the relationship.

- Fourth, networking is communicating with family and friends.

- Lastly, sharing tasks is doing work or household tasks.

- Later, Canary and his colleagues found two more relationship maintenance behaviors: conflict management and advice (Canary & Zelley, 2000).

Additionally, Canary and Stafford also posited four propositions that serve as a conceptual framework for relationship maintenance research (Canary & Stafford, 1994).The first proposition is that relationships will worsen if they are not maintained. The second proposition is that both partners must feel that there are equal benefits and sacrifices in the relationship for it to sustain. The third proposition states that maintenance behaviors depend on the type of relationship. The fourth proposition is that relationship maintenance behaviors can be used alone or as a mixture to affect perceptions of the relationship. Overall, these propositions illustrate the importance and effect that relationship maintenance behaviors can have on relationships.

7.5 Tensions in Relationships

Relationship Dialectics

We know that all relationships go through change. The changes in a relationship are usually dependent on communication. When a relationship starts, there is lots of positive and ample communication between the parties. However, there are times that couples go through a redundant problem, and it is important to learn how to deal with this problem. Partners can’t always know what their significant other desires or needs from them.

Dialectics had been a concept known well too many scholars for many years. They are simply the pushes and pulls that can be found every day in relationships of all types. This perspective examines how we must manage these push-pull tensions that arise, because they cannot be fully resolved. The management of the tensions is usually based on past experiences; what worked for a person in the past will be what they decide to use in the future. These tensions are both contradictory and interdependent because without one, the other is not understood. Dialectical tension is how individuals deal with struggles in their relationship. There are opposing forces or struggles that couples have to deal with (Baxter, 2004; Baxter & Montgomery, 1996).

The overarching premise to dialectical tensions is that all personal ties and relationships are always in a state of constant flux and contradiction. Relational dialectics highlight a “dynamic knot of contradictions in personal relationships; an unceasing interplay between contrary or opposing tendencies” (Griffin, 2009).The concept of contradiction is crucial to understanding relational dialectics. The contradiction is when there are opposing sides to a situation. These contradictions tend to arise when both parties are considered interdependent. Dialectical tension is natural and inevitable. All relationships are complex because human beings are complex, and this fact is reflected in our communicative processes. Baxter and Montgomery argue that tension arises because we are drawn to the antitheses of opposing sides. These contradictions must be met with a “both/and” approach as opposed to the “either/or” mindset. However, the “both/and” approach lends to tension and pressure, which almost always guarantees that relationships are not easy. Below are some different relational dialectics (Baxter, & Montgomery, 1996):

1) Autonomy-Connection

This is where partners seek involvement but not willing to sacrifice their entire identity. For instance, in a marriage, some women struggle with taking their partner’s last name, keeping their maiden name, or combine the two. Often when partners were single, they might have engaged in a girl’s night out or a guy’s night out. When in a committed relationship, one partner might feel left out and want to be more involved. Thus, struggles and conflict occur until the couple can figure out a way to deal with this issue.

2) Predictability–Novelty

This deals with rituals/routines compared to novelty. For instance, for some mothers, it is tough to accept that their child is an adult. They want their child to grow up at the same time it is difficult to recognize how their child has grown up.

3) Transparency-Privacy

Disclosure is necessary, but there is a need for privacy. For some couples, diaries work to keep things private. Yet, there are times when their partner needs to know what can’t be expressed directly through words.

4) Similarity-Difference

This tension deals with self vs. others. Some couples are very similar in their thinking and beliefs. This is good because it makes communication easier and conflict resolution smoother. Yet, if partners are too similar, then they cannot grow. Differences can help couples mature and create stimulation.

5) Ideal-Real

Couples will perceive some things as good and some things as bad. Their perceptions of what is real may interfere or inhibit perceptions of what is real. For instance, a couple may think that their relationship is perfect. But from an outsider, they might think that the relationship is abusive and devastating.

Another example might be that a young dating couple thinks that they do not have to marry each other because it is the ideal and accepted view of taking the relationship to the next phase. Thus, the couples move in together and raise a family without being married. They have deviated from what is an ideal normative cultural script (Baxter, 2006).

6) Judgement-Acceptance

In our friendships, we often feel the simultaneous need to be accepting of our friends for who they are, but also be honest and open with them. In this example, Phoebe wants to help Joey, but she also thinks he is being unreasonable.

Every relationship is fraught with these dialectical tensions. There’s no way around them. However, there are different ways of managing dialectical tensions:

- Denial is where we respond to one end. For example, in a romantic relationship, one partner wants closeness (connection) while the other desires more independence (autonomy). The couple might deny the tension by only focusing on closeness, spending all their time together, and ignoring the need for independence, which might lead to issues later.

- Disorientation is where we feel overwhelmed. We fight, freeze, or leave. For example, a young couple experiencing their first serious conflict may feel overwhelmed by the tension between wanting to stay close (connection) and needing space (autonomy). They might freeze and avoid each other, or have explosive arguments without resolution.

- Alternation is where we choose one end on different occasions. For example, in a friendship, two people balance the need for openness and privacy. They might choose to be very open and share everything during some conversations, but at other times, they respect each other’s need for privacy, alternating between these two extremes depending on the context.

- Recalibration is reframing the situation or perspective. For example, a couple experiencing tension between predictability and novelty reframes their perspective by recognizing that their routine doesn’t have to be boring. Instead, they see stability as a foundation that allows them to introduce new experiences, such as traveling together, without destabilizing their relationship.

- Segmentation is where we compartmentalize different areas. This may sound very similar to alternation, above. For example, in a friendship balancing the need for openness and privacy, the friends may be very open about their romantic relationships, telling each other all of the details of their romantic encounters. But if the subject moves to family relationships, the friends may decide to stay closed off in this area.

- Balance is where we manage and compromise our needs. For example, when a person realizes that their partner cannot be “perfect”, and changes their standards to a more realistic level.

- Integration is blending different perspectives. For example, in a long-distance relationship, the couple integrates the desire for both autonomy and connection by scheduling regular virtual dates but also encouraging each other to pursue individual hobbies and social lives outside of the relationship.

- Reaffirmation is having the knowledge & accepting our differences. For example, partners in a marriage might accept that they will always have different approaches to handling money—one being a saver and the other a spender. They reaffirm their differences by discussing them openly, acknowledging that the tension is a natural and ongoing part of their relationship, and working through it without trying to change each other.

These strategies will come up again as we discuss conflict in chapter 8. Not every couple deals with dialectical tensions in the same way. Some will use a certain strategy during specific situations, and others will use the same strategy every time there is tension.

Wrap Up

Relationships are at the core of human experience, shaping how we connect, grow, and find meaning in our lives. In this chapter, we explored key theories and concepts that help us understand the dynamic nature of interpersonal relationships—from what draws us together to what keeps us connected over time. Theories like interpersonal attraction and social exchange help explain the “why” behind our relationship choices, while frameworks like the stage model of relationships and relational dialectics highlight the fluid, ever-evolving journey of connection.

Relationship maintenance is not a one-time effort but an ongoing process that requires intention, communication, and adaptability. By recognizing the tensions that exist in all relationships and using strategies to balance them, we can build deeper, more resilient connections.

Ultimately, strong relationships are not built solely on attraction or compatibility but on the everyday choices we make—how we show support, manage conflict, negotiate change, and communicate care. Understanding these concepts empowers us to be more mindful, empathetic, and effective in cultivating relationships that enrich our lives and the lives of those around us.

References

Adler, R., Rosenfeld, L. B., & Proctor II, R. F. (2013). Interplay: The process of interpersonal communication. Oxford.Ayers, J. (1983). Strategies to maintain relationships: Their identification and perceived usages. Communication Quarterly, 31(1), 62-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463378309369487

Baxter, L.A. (2004). A tale of two voices: Relational Dialectics Theory. The Journal of Family Communication, 4 (3 & 4), 181-192. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2004.9670130

Baxter, L. A. (2006). Relationship dialectics theory: Multivocal dialogues of family communication. In D. O. Braithwaite & L. A. Baxter (Eds.). Engaging in family communication. (pp. 130-145). Sage.

Baxter, L. A., & Montgomery, B. M. (1996). Relating: Dialogues and dialectics. Guilford Press.

Beebe, S. A., Beebe, S. J., & Redmond, M. V. (2019). Interpersonal Communication: Relating to Others. Pearson.

Canary, D. J., & Stafford. L. (1994). Maintaining relationships through strategic and routine interaction. In D. J. Canary & L. Stafford (Eds.). Communication and relational maintenance (pp. 3-21). Academic Press.

Canary, D. J., & Zelley, E. D. (2000). Current research programs on relational maintenance behaviors. Communication Yearbook, 23, 305-340.

Dindia, K. (2000). Self-disclosure research: Advances through meta-analysis. In M. A. Allen, R. W. Preiss, B. M., Gayle, & N. Burrell (Eds.). Interpersonal communication research: Advances through meta-analysis (pp. 169-186). Erlbaum.

Duck, S. (1988). Relating to others. Dorsey Press.

Duck, S. (1993). Personal Relationships and Personal Constructs: A Study of Friendship Formation. Wiley.

Duck, S. (1994). Steady as (s)he goes: Relational maintenance as a shared meaning system. In D. J. Canary & L. Stafford (Eds.). Communication and relational maintenance (pp. 45-60). Academic Press.

Gamble, T. K.., & Gamble, M. W. (2014). Interpersonal communication: Building connections together. Sage.

Gervis, Z. (2019, May 9). Why the average American hasn’t made a new friend in five years. SWNS digital. https://tinyurl.com/yxtc2htg

Goddard, I. (2023, October 12). What does friendship look like in America? Pew Research Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/10/12/what-does-friendship-look-like-in-america/

Goddard, I., & Parker, K. (2025, January 16). Men, women and social connections. Pew Research Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2025/01/16/men-women-and-social-connections/

Graziano, W. G., & Bruce, J. W. (2008). Attraction and the initiation of relationships: A review of the empirical literature. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel, and J. Harvey (Eds.),.Handbook of Relationship Initiation, Psychology Press.

Griffin, E.M. (2009). A first look at communication theory. McGraw Hill, pg. 115.

Knapp, M. L. (1984). Interpersonal communication and human relationships. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Knapp, M. L., & Vangelisti, A. L. (1992). Interpersonal communication and human behavior (2nd ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Punyanunt-Carter, N. M. (2004). Reported affectionate communication and satisfaction in marital and dating relationships. Psychological Reports, 166(3), 1049-1055. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.95.3f.1154-1160

Samovar, L. A., & Porter, R. E. (1995). Communication between cultures (2nd ed.). Wadsworth, p. 188.

Stafford, L. (2008). Social exchange theories. In L. A. Baxter & D. O. Braithwaite (Eds.), Engaging theories in interpersonal communication: Multiple perspectives (pp. 377-389). Sage.

Thibaut, J. W., & Kelley, H. H. (1959). The social psychology of groups. Wiley.

Figures

Figure 7.1. Rinalidi, E. (2017). Zac Efron at the Baywatch Red Carpet Premier Sydney Australia. https://www.flickr.com/photos/evarinaldiphotography/34732955995/in/album-72157680824643334/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68196882

Figure 7.2. Krukau, Y. (2021). Women singing together. Pexels license. Retrieved from https://www.pexels.com/photo/women-singing-together-9008830/

Figure 7.3. Jopwell. (2019). Woman in a blue suit jacket. Pexels license. Retrieved from https://www.pexels.com/photo/woman-in-blue-suit-jacket-2422293/

Figure 7.4. Knapp and Vangelisti Model of Relationships. Interpersonal Communication Copyright © by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt.

Figure 7.5 Relationship Maintenance Behaviors. Interpersonal Communication Copyright © by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt.

This chapter was adapted from Building and Maintaining Relationships in Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench, Narissa M. Punyanunt-Carter, and Katerina S. Thweatt, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 license. It has been modified and expanded by the Editor to fit the context of Communication in the Real World, and is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Tensions in a relationship where individuals need to deal with integration vs. separation, expression vs. privacy, and stability vs. change.

Expectations about how the relationship will function.

Introduction

10.1 Introduction to Public Speaking

Public speaking is a vital area of study within the broader field of communication. It focuses on the intentional, structured, and purposeful act of delivering messages to an audience—whether that audience is large or small, formal or informal, in person or online. Public speaking draws on principles from interpersonal, intercultural, and rhetorical communication, blending the art of persuasion with the science of message design and delivery (West & Turner, 2024).

Strong public speaking skills are essential in many areas of life. Whether you're presenting a project in class, giving a toast at a wedding, interviewing for a job, pitching a new idea at work, or advocating for a cause you care about, your ability to clearly and confidently express your thoughts can make a lasting impact. Public speaking helps individuals organize ideas effectively, connect with diverse audiences, and influence others through storytelling, evidence, and strategic delivery.

This is why public speaking is a foundational part of any introductory communication course. Learning how to prepare and deliver speeches not only helps students overcome anxiety and gain confidence, but also builds critical thinking, listening, and collaboration skills. In today's fast-paced, media-rich world, being an effective speaker is not just about talking—it's about engaging, informing, and inspiring others. By studying public speaking, students prepare to be thoughtful communicators in both their professional and personal lives.

The remainder of this chapter will help you to get started with public speaking and covers speech-making topics such as: 1) identifying the best topic, 2) determining how to best support your speech, 3) how to organize or structure your public speaking messages, and 4) written communication tools such as outlines.

10.2 Selecting and Narrowing a Topic

Many steps go into the speech-making process. Many people do not approach speech preparation in an informed and systematic way, which results in many poorly planned or executed speeches that are not pleasant to sit through as an audience member and do not reflect well on the speaker. Good speaking skills can help you stand out from the crowd in increasingly competitive environments. While a polished delivery is important, good speaking skills must be practiced much earlier in the speech-making process (James Madison University Writing Center, 2021).

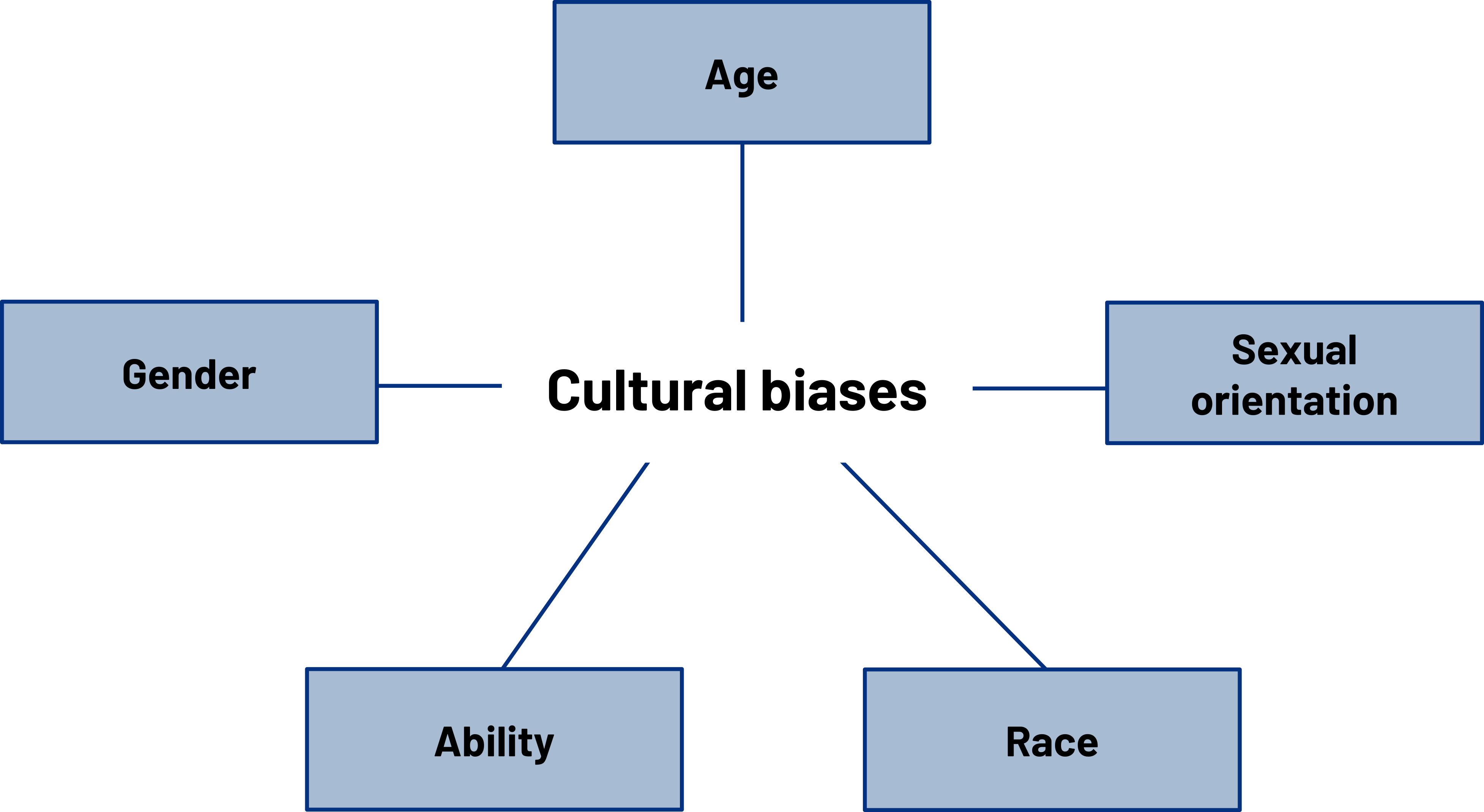

10.2.1 Analyze Your Audience

Audience analysis is key for a speaker to achieve their speech goal. One of the first questions you should ask yourself is “Who is my audience?” While there are some generalizations you can make about an audience, a competent speaker always assumes there is a diversity of opinion and background among his or her listeners. You cannot assume from looking that everyone in your audience is the same age, race, sexual orientation, religion, or many other factors. Even if you did have a homogenous audience, with only one or two people who do not match up, you should still consider those one or two people. Of course, a speaker could still unintentionally alienate certain audience members, especially in persuasive speaking situations. While this may be unavoidable, speakers can still think critically about what content they include in the speech and the effects it may have (James Madison University Communication Center, 2021).

Here are some ways you can think about audience analysis:

- Demographic Audience Analysis: Demographics are broad sociocultural categories, such as age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, education level, religion, ethnicity, and nationality used to segment a larger population. Since you are always going to have diverse demographics among your audience members, it would be unwise to focus solely on one group over another. Being aware of audience demographics is useful because you can tailor and vary examples in order to appeal to different groups of people (James Madison University Communication Center, 2021).

- Psychological Audience Analysis: Psychological audience analysis considers the audience’s psychological dispositions (thoughts, attitudes, experience) toward the topic, the speaker, and the occasion as well as how their attitudes, beliefs, and values inform those dispositions (Dlugan, 2012). What is your audience's mindset coming into the speech? Do they like or dislike the topic? How do they feel about you? All these factors can impact the success of your speech. Here are some things to consider when choosing your topic and considering what to cover in your speech:

- Motivation for being there. The circumstances that led your audience to attend your speech will affect their view of the occasion (Dlugan, 2012).

-

Figure 10.1: Mandatory work meetings are an example of captive audiences. A captive audience includes people who are required to attend your presentation. Mandatory meetings are common in workplace settings. Whether you are presenting for a group of your employees, coworkers, classmates, or even residents in your dorm if you are a resident advisor, you should not let the fact that the meeting is required give you license to give a half-hearted speech. In fact, you may want to build common ground with your audience to overcome any potential resentment for the required gathering. In your speech class, your classmates are captive audience members.

- A voluntary audience includes people who have decided to come hear your speech. To help adapt to a voluntary audience, ask yourself what the audience members expect (Dlugan, 2012). Why are they here? If they have decided to come and see you, they must be interested in your topic or you as a speaker. Perhaps you have a reputation for being humorous, being able to translate complicated information into more digestible parts, or being interactive with the audience and responding to questions. Whatever the reason or reasons, it is important to make sure you deliver on those aspects. If people are voluntarily giving up their time to hear you, you want to make sure they get what they expected.

-

- Feelings about YOU, the Speaker. The audience may or may not have preconceptions about you as a speaker. One way to engage positively with your audience is to make sure you establish your credibility. In terms of credibility, you want the audience to see you as competent, trustworthy, and engaging. If the audience is already familiar with you, they may already see you as a credible speaker because they have seen you speak before, have heard other people evaluate you positively, or know that you have credentials and/or experience that make you competent. If you know you have a reputation that is not as positive, you will want to work hard to overcome those perceptions. To establish your trustworthiness, you want to incorporate good supporting material into your speech, verbally cite sources, and present information and arguments in a balanced, non-coercive, and non-manipulative way. To establish yourself as engaging, you want to have a well-delivered speech, which requires you to practice, get feedback, and practice some more. Your verbal and nonverbal delivery should be fluent and appropriate to the audience and occasion.

- Knowledge. When considering your audience’s disposition toward your topic, you want to assess your audience’s knowledge of the subject. You would not include a lesson on calculus in an introductory math course. You also would not go into the intricacies of a heart transplant to an audience with no medical training.

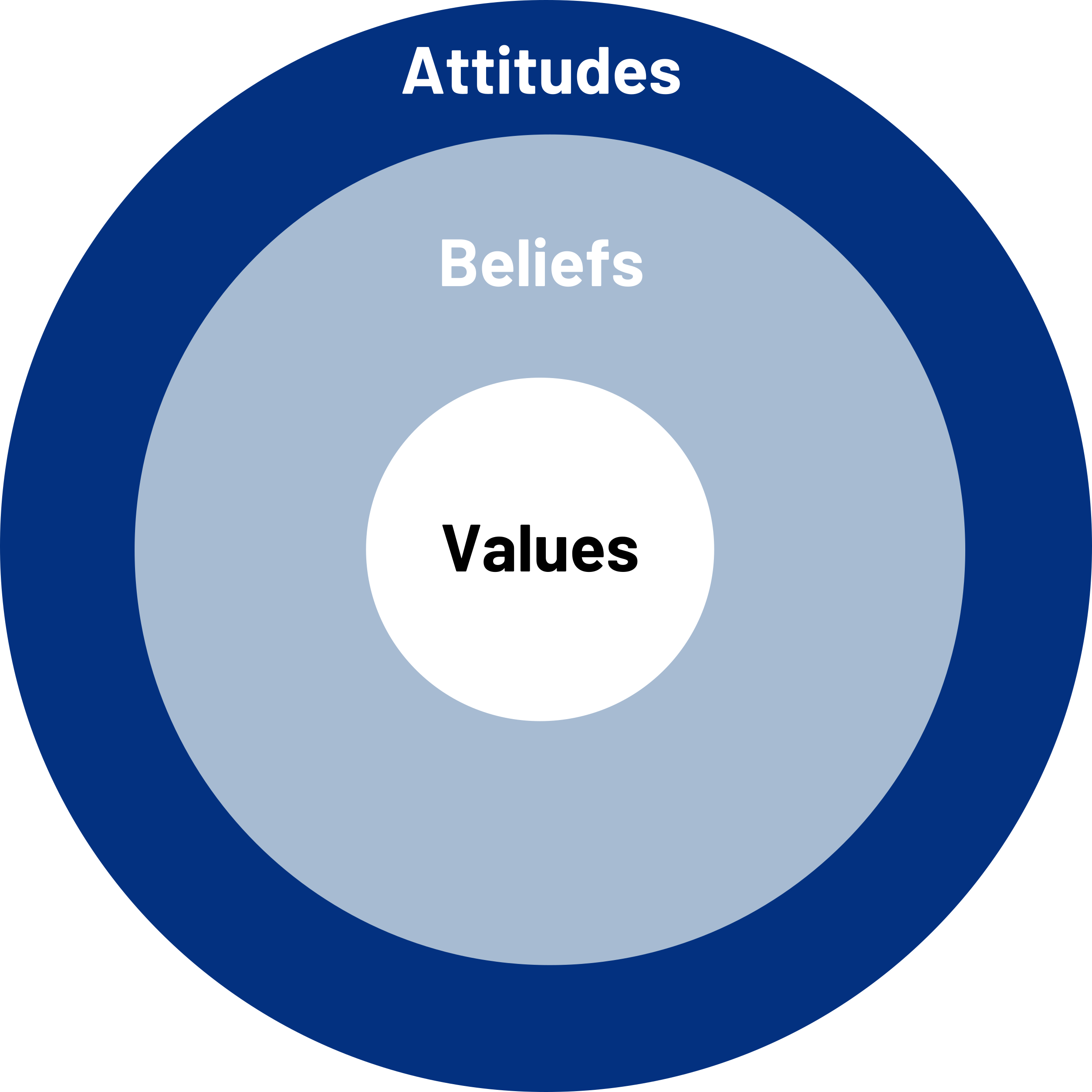

- Perception. A final aspect of psychological audience analysis involves considering the audience’s attitudes, beliefs, and values, as they will influence all the perceptions mentioned previously (Dlugan, 2012). As you can see in the figure below, think of our attitudes, beliefs, and values as layers that make up our perception and knowledge.

- Motivation for being there. The circumstances that led your audience to attend your speech will affect their view of the occasion (Dlugan, 2012).

At the outermost level, attitudes are our likes and dislikes, and they are easier to influence than beliefs or values because they are often reactionary (Dlugan, 2012). If you have ever followed the approval rating of a politician, you know that people’s likes and dislikes change frequently and can change dramatically based on recent developments. This is also true interpersonally. For those of you who have siblings, think about how you can go from liking your sisters or brothers, maybe because they did something nice for you, to disliking them because they upset you. This seesaw of attitudes can go up and down over the course of a day or even a few minutes, but it can still be useful for a speaker to consider. If there is something going on in popular culture or current events that has captured people’s attention and favor or disfavor, then you can tap into that as a speaker to better relate to your audience.

When considering beliefs, we are dealing with what we believe “is or isn’t” or “true or false.” We come to hold our beliefs based on what we are taught, experience for ourselves, or believe (Dlugan, 2012). Our beliefs change if we encounter new information or experiences that counter previous ones. As people age and experience more, their beliefs are likely to change, which is natural.

Our values deal with what we view as right or wrong, good or bad (Dlugan, 2012). Our values do change over time but usually because of a life transition or life-changing event such as a birth, death, or trauma. For example, when many people leave their parents’ control for the first time and move away from home, they have a shift in values that occurs as they make this important and challenging life transition. In summary, audiences enter a speaking situation with various psychological dispositions, and considering what those may be can help speakers adapt their messages and better meet their speech goals.

10.2.2 General Purpose

Your speeches will usually fall into one of three categories. In some cases, we speak to inform, meaning we attempt to teach our audience using factual objective evidence. In other cases, we speak to persuade, as we try to influence an audience’s beliefs, attitudes, values, or behaviors. Last, we may speak to entertain or amuse our audience. In summary, the general purpose of your speech will be to inform, to persuade, or to entertain.

You can see various topics that may fit into the three general purposes for speaking in the table below “General Purposes and Speech Topics”. Some of the topics listed could fall into another general purpose category depending on how the speaker approached the topic, or they could contain elements of more than one general purpose. For example, you may have to inform your audience about your topic in one main point before you can persuade them, or you may include some entertaining elements in an informative or persuasive speech to help make the content more engaging for the audience. There should not be elements of persuasion included in an informative speech, however, since persuading is contrary to the objective approach that defines an informative general purpose. In any case, while there may be some overlap between general purposes, we place most speeches into one of the categories based on the overall content of the speech.

| Inform | Persuade | Entertain | |

| Definition | to teach, define, describe, explain, or enhance knowledge in some way (increase knowledge and understanding) | to change or reinforce ideas, or urge your audience to do something (influence thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors) | to amuse, share enjoyment, or make others laugh and smile (spark positive emotions) |

| General Purpose Statement (Example Topic: Travel) | By the end of this speech, the audience will be able to describe the most popular travel destinations in the U.S. | By the end of this speech, the audience will plan a trip abroad. | By the end of this speech my audience will be laughing at my travel misadventures. |

10.2.3 Choosing a Topic

Once you have determined (or been assigned) your general purpose, you can begin the process of choosing a topic. In class, an instructor may give you the option of choosing any topic for your informative or persuasive speech, but in most academic, professional, and personal settings, there will be some parameters set that will help guide your topic selection. It is likely that speeches will be organized around the content covered in the class. Speeches delivered at work will usually be directed toward a specific goal, such as welcoming new employees, informing employees about changes in workplace policies, or presenting quarterly sales figures. We are also usually compelled to speak about specific things in our personal lives, like addressing a problem at our child’s school by speaking out at a school board meeting. In short, it is not often that you will be starting from scratch when you begin to choose a topic.

Whether you have received parameters that narrow your topic range or not, the first step in choosing a topic is brainstorming (James Madison University Writing Center, 2021). Brainstorming involves generating many potential topic ideas in a fast-paced and nonjudgmental manner. Brainstorming can take place multiple times, as you narrow your topic. For example, you may begin by brainstorming a list of your personal interests that you can narrow down to a speech topic. It makes sense that you will enjoy speaking about something that you care about or find interesting. The research and writing will be more interesting, and the delivery will be easier since you will not have to fake enthusiasm for your topic. Speaking about something you are familiar with and interested in can also help you manage speaking anxiety.

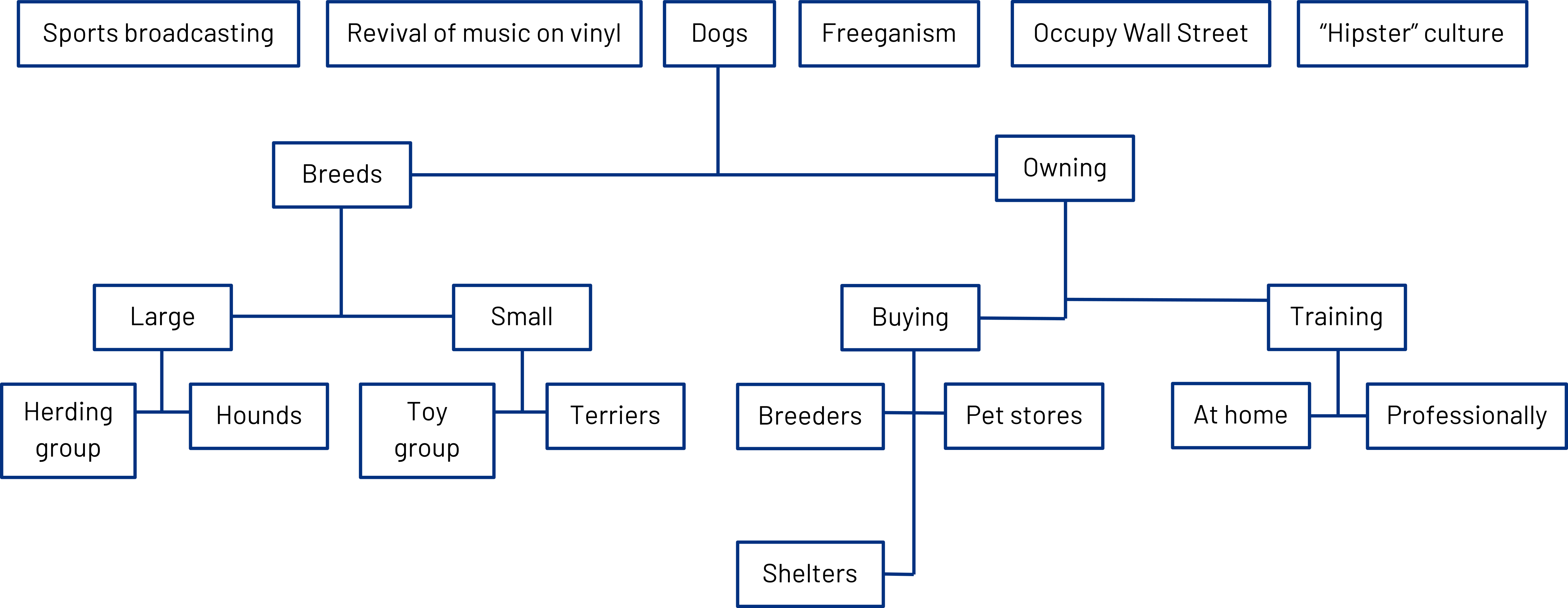

While it is good to start with your personal interests, some speakers may be stuck here if they do not feel like they can make their interests relevant to the audience. In that case, you can look around for ideas. If your topic is something being discussed in newspapers, on television, in the lounge at school, or around your family’s dinner table, then it is likely to be of interest and be relevant, since it is current. Figure 10.3 shows how brainstorming works in stages. A list of topics that interest the speaker are on the top row. The speaker can brainstorm subtopics for each idea to see which one may work the best. In this case, the speaker could decide to focus his or her informative speech on three common ways people come to own dogs: through breeders, pet stores, or shelters.

Overall, you can follow these tips as you select and narrow your topic:

- Brainstorm topics that you are familiar with, interest you, and/or are currently topics of discussion.

- Choose a topic appropriate for the assignment/occasion.

- Choose a topic that you can make relevant to your audience.

- Choose a topic that you have the resources to research (access to information, people to interview, etc.).

10.2.4 Specific Purpose

Once you have brainstormed, narrowed, and chosen your topic, you can begin to draft your specific purpose statement. Your specific purpose is a one-sentence statement that includes the objective you want to accomplish in your speech. You do not speak aloud your specific purpose during your speech; you use it to guide your researching, organizing, and writing. A good specific purpose statement is 1) audience centered, 2) agrees with the general purpose, 3) addresses one main idea, and 4) is realistic.

An audience-centered specific purpose statement usually contains an explicit reference to the audience—for example, “my audience” or “the audience.” Since a speaker may want to see if he or she effectively met his or her specific purpose, write the objective so that it could be measured or assessed. Moreover, since a speaker actually wants to achieve his or her speech goal, the specific purpose should also be realistic. You will not be able to teach the audience a foreign language or persuade an atheist to Christianity in a six- to nine-minute speech. The following is a good example of a good specific purpose statement for an informative speech: “By the end of my speech, the audience will be better informed about the effects the green movement has had on schools.” The statement is audience-centered and matches with the general purpose by stating, “The audience will be better informed.” The speaker could also test this specific purpose by asking the audience to write down, at the end of the speech, three effects the green movement has had on schools.

10.2.5 Thesis Statement

Your thesis statement is a one-sentence summary of the central idea of your speech that you either explain or defend (James Madison University Communication Center, 2021). You would explain the thesis statement for an informative speech, since these speeches are based on factual, objective material. You would defend your thesis statement for a persuasive speech, because these speeches are argumentative and your thesis should clearly indicate a stance on a particular issue. In order to make sure your thesis is argumentative and your stance clear, it is helpful to start your thesis with the words “I believe.” When starting to work on a persuasive speech, it can also be beneficial to write out a counterargument to your thesis to ensure that it is arguable.

The thesis statement is different from the specific purpose in two main ways. First, the thesis statement is content centered, while the specific purpose statement is audience centered. Second, the thesis statement is incorporated into the spoken portion of your speech, while the specific purpose serves as a guide for your research and writing and an objective that you can measure (Goodwin, 2017). A good thesis statement is declarative, agrees with the general and specific purposes, and focuses and narrows your topic. Although you will likely end up revising and refining your thesis as you research and write, it is good to draft a thesis statement soon after drafting a specific purpose to help guide your progress. As with the specific purpose statement, your thesis helps ensure that your research, organizing, and writing are focused so you don’t end up wasting time with irrelevant materials. Keep your specific purpose and thesis statement handy (drafting them at the top of your working outline is a good idea) so you can reference them often. The following examples show how a general purpose, specific purpose, and thesis statement match up with a topic area:

Example 1

Topic: My Craziest Adventure

General purpose: To Entertain

Specific purpose: By the end of my speech, the audience will appreciate the lasting memories that result from an eighteen-year-old visiting New Orleans for the first time.

Thesis statement: New Orleans offers young tourists many opportunities for fun and excitement.

Example 2

Topic: Renewable Energy

General purpose: To Inform

Specific purpose: By the end of my speech, the audience will be able to explain the basics of using biomass as fuel.

Thesis statement: Biomass is a renewable resource that releases gases that can be used for fuel.

Example 3

Topic: Privacy Rights

General purpose: To Persuade

Specific purpose: By the end of my speech, my audience will believe that parents should not be able to use tracking devices to monitor their teenage child’s activities.

Thesis statement: I believe that it is a violation of a child’s privacy to be electronically monitored by his or her parents.

10.3 Researching and Supporting Your Speech

We live in an age where access to information is more convenient than ever before. The days of photocopying journal articles in the stacks of the library or looking up newspaper articles on microfilm are over for most. Yet, even though we have all this information readily available, research skills are more important than ever. Our challenge now is not accessing information but discerning what information is credible and relevant. Even though it may sound inconvenient to have to go physically to the library, students who did research before the digital revolution did not have to worry as much about discerning. If you found a source in the library, you could be assured of its credibility because a librarian had subscribed to or purchased that content. When you use Internet resources like Google or Wikipedia, you have no guarantees about some of the content that comes up.

10.3.1 Finding Supporting Material

As was noted earlier, it is good to speak about something with which you are already familiar. So existing knowledge forms the first step of your research process. Depending on how familiar you are with a topic, you will need to do more or less background research before you actually start incorporating sources to support your speech. Background research is just a review of summaries available for your topic that helps refresh or create your knowledge about the subject. It is not the more focused and academic research that you will actually use to support and verbally cite in your speech.

Your first step for research in college should be library resources, not Google, Bing, or other general search engines. In most cases, you can still do your library research from the comfort of a computer, which makes it as accessible as Google but gives you much better results. Excellent and underutilized resources at college and university libraries are reference librarians. Reference librarians are not like the people who likely staffed your high school library. They are information-retrieval experts. At most colleges and universities, you can find a reference librarian who has at least a master’s degree in library and information sciences, and at some larger or specialized schools, reference librarians have doctoral degrees. Research can seem like a maze, and reference librarians can help you navigate the maze. There may be dead ends, but there is always another way around to reach the end goal.

Unfortunately, many students hit their first dead end and give up or assume that there is not enough research out there to support their speech. If you have thought of a topic to do your speech on, someone else has thought of it, too, and people have written and published about it. Reference librarians can help you find that information (Matook, 2020). Meet with a reference librarian face-to-face and take your assignment sheet and topic idea with you. In most cases, students report that they came away with more information than they needed, which is good because you can then narrow that down to the best information. If you cannot meet with a reference librarian face-to-face, many schools now offer the option to do a live chat with a reference librarian, and you can contact them by e-mail or phone.

Aside from the human resources available in the library, you can also use electronic resources such as library databases. Library databases help you access more credible and scholarly information than what you will find using general Internet searches. These databases are quite expensive, and you cannot access them as a regular citizen without paying for them. Luckily, some of your student fee dollars go to pay for subscriptions to these databases so that you can access them as a student. Through these databases, you can access newspapers, magazines, journals, and books from around the world. Of course, libraries also house stores of physical resources like DVDs, books, academic journals, newspapers, and popular magazines (James Madison University Libraries, 2021). You can usually browse your library’s physical collection through an online catalog search. A trip to the library to browse is especially useful for books. Since most university libraries use the Library of Congress classification system, books are organized by topic. That means if you find a good book using the online catalog and go to the library to get it, you should take a moment to look around that book, because the other books in that area will be topically related. On many occasions, I have used this tip and gone to the library for one book but left with several.

Although Google is not usually the best first stop for conducting college-level research, Google Scholar is a separate search engine that narrows results down to scholarly materials. This version of Google has improved much over the past few years and has served as a good resource for my research, even for this book. A strength of Google Scholar is that you can easily search for and find articles not confined to a particular library database. The pool of resources you are searching in is much larger than what you would find by using a library database. The challenge is that you have no way of knowing if the articles that come up are available to you in full-text format. As noted earlier, you will find most academic journal articles in databases that require users to pay subscription fees. Therefore, you are often only able to access the abstracts of articles or excerpts from books that come up in a Google Scholar search. You can use that information to check your library to see if the article is available in full-text format, but if it is not, you have to go back to the search results. When you access Google Scholar on a campus network that subscribes to academic databases, however, you can sometimes click through directly to full-text articles. Although this resource is still being improved, it may be a useful alternative or backup when other search strategies are leading to dead end.

10.3.2 Types of Sources

Periodicals

Periodicals include magazines and journals that are published periodically. Many library databases can access periodicals from around the world and from years past. A common database is Academic Search Premiere (a similar version is Academic Search Complete). Many databases, like this one, allow you to narrow your search terms, which can be very helpful as you try to find good sources that are relevant to your topic. You may start by typing a key word into the first box and searching. Sometimes a general search like this can yield thousands of results, which you obviously would not have time to look through. In this case, you may limit your search to results that have your keyword in the abstract, which is the author-supplied summary of the source. If there are still too many results, you may limit your search to results that have your keyword in the title. At this point, you may have reduced those ten thousand results down to a handful, which is much more manageable.

Within your search results, you will need to distinguish between magazines and academic journals. In general, academic journals are considered more scholarly and credible than magazines because most of the content in them is peer reviewed. The peer-review process is the most rigorous form of review, which takes several months to years and ensures that the information that is published has been vetted and approved by numerous experts on the subject. Academic journals are often affiliated with professional organizations rather than for-profit corporations, and neither authors nor editors are paid for their contributions.

Newspapers and Books

Newspapers and books can be excellent sources but must still be evaluated for relevance and credibility. Newspapers are good for topics that are developing quickly, as they are updated daily. While there are well-known newspapers of record like the New York Times, smaller local papers can also be credible and relevant if your speech topic does not have national or international reach. You can access local, national, and international newspapers through electronic databases like LexisNexis.

To evaluate the credibility of a book, you will want to know some things about the author. You can usually find this information at the front or back of the book. If an author is a credentialed and recognized expert in his or her area, the book will be more credible. However, just because someone wrote a book on a subject does not mean he or she is the most credible source. The publisher of a book can also be an indicator of credibility. Books published by university/academic presses (University of Chicago Press, Duke University Press) are considered more credible than books published by trade presses (Penguin, Random House), because they are often peer reviewed and they are not primarily profit driven.

Reference Tools

The transition to college-level research means turning more toward primary sources and away from general reference materials. Primary sources are written by people with firsthand experiences or by researchers/scholars who conducted original research (National WW II Museum, n.d.). Unfortunately, many college students are reluctant to give up their reliance on reference tools like dictionaries and encyclopedias. While reference tools like dictionaries and encyclopedias are excellent for providing a speaker with a background on a topic, they should not be the foundation of your research unless they are academic and/or specialized.

Dictionaries are handy tools when we are not familiar with a particular word. However, citing a dictionary like Merriam-Webster’s as a source in your speech is often unnecessary (please don't do this). A dictionary is useful when you need to challenge a Scrabble word, but it is not the best source for college-level research.

Many students have relied on encyclopedias for research in high school, but most encyclopedias, like World Book, Encarta, or Britannica, are not primary sources. Instead, they are examples of secondary sources that aggregate, or compile, research done by others in a condensed summary (James Madison University Libraries, 2019). Reference sources like encyclopedias are excellent resources to get you informed about the basics of a topic, but at the college level, primary sources are expected. Many encyclopedias are internet-based, which makes them convenient, but they are still not primary sources, and their credibility should be even more scrutinized.

Wikipedia revolutionized how many people retrieve information and pioneered an open-publishing format that allowed a community of people to post, edit, and debate content. While this is an important contribution to society, Wikipedia is not considered a scholarly or credible source. Like other encyclopedias, Wikipedia should not be used in college-level research, because it is not a primary source. In addition, since its content can be posted and edited by anyone, we cannot be sure of the credibility of the content. Even though there are self-appointed “experts” who monitor and edit some of the information on Wikipedia, we cannot verify their credentials or the review process that information goes through before it is posted.

Interviews

When conducting an interview for a speech, you should access a person who has expertise in or direct experience with your speech topic. If you follow the suggestions for choosing a topic that were mentioned earlier, you may already know something about your speech topic and may have connections to people who would be good interview subjects. Previous employers, internship supervisors, teachers, community leaders, or even relatives may be appropriate interviewees, given your topic. If you do not have a connection to someone you can interview, you can often find someone via the Internet who would be willing to answer some questions. Many informative and persuasive speech topics relate to current issues, and most current issues have organizations that represent their needs.

Open-ended questions cannot be answered with a “yes” or “no” but they can provide descriptions and details that will add to your speech. Quotes and paraphrases from your interview can add a personal side to a topic or at least convey potentially complicated information in a more conversational and interpersonal way. Closed questions can be answered with one or two words and can provide a starting point to get to information that is more detailed. However, the interviewer must have prepared follow-up questions. Unless the guidelines or occasion for your speech suggest otherwise, you should balance your interview data with the other sources in your speech. Do not let your references to the interview take over your speech. (And yes, you should cite your references throughout your speech, including primary interviews. More on that later!)

Websites

We already know that utilizing library resources can help you automatically filter out content that may not be scholarly or credible, since the content in research databases is selected and restricted. However, some information may be better retrieved from websites. Even though research databases and websites are electronic sources, two key differences between them may affect their credibility (Brigham Young University Library, 2021).

First, most of the content in research databases is or was printed but was converted to digital formats for easier and broader access. In contrast, most of the content on websites has not been printed. Second, most of the content on research databases has gone through editorial review, which means a professional editor or a peer editor has reviewed the material to make sure it is credible and worthy of publication. Most content on websites is not subjected to the same review process, as just about anyone with internet access can self-publish information on a personal website, blog, wiki, or social media page. Therefore, what sort of information may be better retrieved from websites, and how can we evaluate the credibility of a website?