8 Chapter 8: Conflict in Relationships

Introduction

What do you do when you perceive a disagreement with someone close to you? Have you ever attempted to confront a family member about an important issue, only to have them shift the topic or joke it off? These situations can be incredibly frustrating—but they’re also quite common. In this chapter we’ll discuss interpersonal conflict: a perceived or expressed disagreement between two or more interdependent parties. Conflict is a natural part of human interaction, as conflict can arise from differences in opinions, miscommunication, or perceived threats to one’s identity or goals. While many people view conflict as negative, it is an essential aspect of communication. When handled well, conflict can strengthen relationships, foster mutual understanding, and promote creative problem-solving. We’ll begin by breaking down the definition of conflict, examining two perspectives on its role in relationships, and exploring its positive and negative functions. Later in the chapter, we’ll look at emotional dynamics in conflict and strategies for navigating disagreements constructively.

8.1 Understanding Conflict

The term conflict can be difficult to define precisely. Scholars have proposed many definitions over time, but generally speaking, conflict, is an interactive process occurring when conscious beings (individuals or groups) have opposing or incompatible actions, beliefs, goals, ideas, motives, needs, objectives, obligations resources and/or values. Let’s unpack that definition a bit:

-

Conflict is inherently communicative—it happens through interaction.

-

It involves at least two conscious, thinking parties—individuals or groups.

-

It arises from incompatibility, whether that’s over beliefs, goals, resources, or any number of other areas.

This definition spans a wide range of disagreements—from minor differences of opinion to intense, emotionally charged disputes. In the next section, we’ll break this down further and explore why understanding conflict matters in communication.

8.1.1 Defining Interpersonal Conflict

According to Cahn and Abigail (2014), interpersonal conflict requires four factors to be present:

- the conflict parties are interdependent,

- they have the perception that they seek incompatible goals or outcomes or they favor incompatible means to the same ends,

- the perceived incompatibility has the potential to adversely affect the relationship leaving emotional residues if not addressed, and

- there is a sense of urgency about the need to resolve the difference.

Let’s look at each of these parts of interpersonal conflict separately.

People are Interdependent

According to Cahn and Abigail, “interdependence occurs when those involved in a relationship characterize it as continuous and important, making it worth the effort to maintain” (2014). From this perspective, interpersonal conflict occurs when we are in some kind of relationship with another person. For example, it could be a relationship with a parent/guardian, a child, a coworker, a boss, a spouse, etc. In each of these interpersonal relationships, we generally see ourselves as having long-term relationships with these people that we want to succeed. For example, if you argue with a stranger on the subway, it may be a disagreement, but not an interpersonal conflict. Without interdependence, the stakes are lower and the connection less meaningful.

People Perceive Differing Goals/Outcomes of Means to the Same Ends

An incompatible goal occurs when two people want different things. For example, imagine you and your best friend are thinking about going to the movies. They want to see a big-budget superhero film, and you’re more in the mood for an independent artsy film. In this case, you have pretty incompatible goals (movie choices). You can also have incompatible means to reach the same end. Incompatible means, in this case, “occur when we want to achieve the same goal but differ in how we should do so” (Cahn & Abigail, 2014). For example, you and your best friend agree on going to the same movie, but not about at which theatre you should see the film.

Conflict Can Negatively Affect the Relationship if Not Addressed

Poorly managed conflict can damage relationships. Consider these examples of mismanagement:

- One person dominates while the other caves.

- Someone yells or uses insults.

- One partner manipulates through lies or half-truths.

- Both parties refuse to compromise.

- One partner avoids the issue altogether.

When conflicts are handled destructively, they can erode liking, trust, and emotional investment. Over time, this may lead to avoidance, resentment, or even the end of the relationship. Later in this chapter, we’ll examine aggressive and avoidant conflict behaviors in more detail.

There is a Sense of Urgency

Finally, interpersonal conflicts involve a pressing need for resolution. If left unresolved, conflicts can escalate or simmer beneath the surface.

Now, some people let conflicts stir and rise over many years that can eventually boil over, but these types of conflicts when they arise generally have some other kind of underlying conflict that is causing the sudden explosion. For example, imagine your spouse has a particularly quirky habit. For the most part, you ignore this habit and may even make a joke about the habit. Finally, one day you just explode and demand the habit must change. Now, it’s possible that you let this conflict build for so long that it finally explodes. It’s kind of like a geyser. According to Yellowstone National Park (2015), here’s how a geyser works:

The looping chambers trap steam from the hot water. Escaped bubbles from trapped steam heat the water column to the boiling point. When the pressure from the trapped steam builds enough, it blasts, releasing the pressure. As the entire water column boils out of the ground, more than half the volume is this steam. The eruption stops when the water cools below the boiling point.

In the same way, sometimes people let irritations or underlying conflict percolate inside of them until they reach a boiling point, which leads to the eventual release of pressure in the form of a sudden, out of nowhere conflict. In this case, even though the conflict has been building for some time, the eventual desire to make this conflict known to the other person does cause an immediate sense of urgency for the conflict to be solved.

8.1.2 Two Perspectives on Conflict

As with most areas of interpersonal communication, no single perspective exists in the field related to interpersonal conflict. There are generally two very different perspectives that one can take (see Simons, 1972). On the one hand, you had scholars who see conflict as a disruption in a normal working system, which should be avoided. On the other hand, some scholars view conflict as a normal part of human relationships. Let’s look at each of these in this section.

Conflict as Disruption

The first major perspective on conflict views it as inherently disruptive and potentially harmful to relationships and social harmony. This perspective, often aligned with collectivistic cultures, emphasizes the importance of group cohesion, maintaining relationships, and avoiding direct confrontation. According to McCroskey and Wheeless (1976), conflict in interpersonal relationships is seen as the breakdown of affinity—the erosion of mutual attraction, the perception of incompatibility, and the development of disrespect between individuals. From this viewpoint, conflict is not simply a disagreement over an issue but a deeper disruption of social bonds, often leading to negative emotions and damaged relationships. Collectivistic cultures, which prioritize harmony and interdependence, tend to view conflict as something to be avoided whenever possible, as it threatens the stability and well-being of the group.

From this perspective, conflict is often managed through indirect communication, compromise, or avoidance, with an emphasis on preserving relationships over winning the argument. When conflict escalates and is allowed to fester, it is compared to a wound that worsens without care. While disagreements can be addressed and resolved in a way that allows both parties to save face, conflicts are seen as far more damaging and may require significant effort to manage without causing lasting harm to the relationship.

Conflict as Normal

The second perspective of the concept of conflict is very different from the first one. According to this perspective, conflict is a normal and an inevitable part of life, essential for the growth of relationships (Cahn & Abigail, 2014). From this viewpoint, conflict is a natural aspect of human interaction, where individuals with different perspectives and needs come together to negotiate, collaborate, and find solutions. In fact, one could ask whether it is possible for relationships to grow without conflict. Successfully managing and resolving conflicts can make relationships healthier, fostering mutual understanding and trust.

In this approach, conflict is seen as neither inherently good nor bad, but rather a tool that can be used for constructive or destructive purposes, depending on how it is handled. When managed well, conflict can offer numerous benefits to individuals and relationships. It helps people find common ground, develop better conflict management skills for the future, and gain a deeper understanding of one another. Conflict often leads to creative solutions to problems, providing opportunities for open and honest discussions that build trust. Moreover, navigating conflict encourages personal growth, improves communication skills, and enhances emotional intelligence. It also allows individuals to set healthy boundaries, assert their needs, and practice effective communication strategies.

When viewed from this perspective, conflict is an invaluable resource in relationships, offering opportunities for learning, development, and connection. However, for conflict to be truly beneficial, both parties must engage in prosocial conflict management strategies—working together to ensure the conflict leads to positive outcomes for all involved.

8.2 Power and Influence

One of the primary reasons we engage in a variety of interpersonal relationships over our lifetimes is to influence others. Whether we realize it or not, we live in a world where we’re constantly trying to accomplish goals—big or small—and getting others on board with those goals is often essential. Influence is a key part of social survival. We define influence when an individual or group of people alters another person’s thinking, feelings, and/or behaviors through accidental, expressive, or rhetorical communication (Wrench, McCrosky, & Richmond, 2008). Notice this definition of influence is one that focuses on the importance of communication within the interaction. Within this definition, we discuss three specific types of communication: unintentional, expressive, or rhetorical.

First, we have unintentional communication, or when we send messages to another person without realizing those messages are being sent. Imagine you are walking on campus and notice a table set up for a specific charity. A person who you really respect is hanging out at the table laughing and smiling, so you decide to donate a dollar to the charity. The person who was just hanging out at the table influenced your decision to donate. They could have just been talking to another friend and may not have even really been a supporter of the charity, but their presence was enough to influence your donation. At the same time, we often influence others to think, feel, and behave in ways they wouldn’t have unconsciously. A smile, a frown, a head nod, or eye eversion can all be nonverbal indicators to other people, which could influence them.

The second type of communication we can have is expressive or emotionally-based communication. Our emotional states can often influence other people. If we are happy, others can become happy, and if we are sad, others may avoid us altogether. Maybe you’ve walked into a room and seen someone crying, so you ask, “Are you OK?” Instead of responding, the person just turns and glowers at you, so you turn around and leave. With just one look, this person influenced your behavior.

The final type of communication, rhetorical communication, involves purposefully creating and sending messages to another person in the hopes of altering another person’s thinking, feelings, and/or behaviors. Unintentional communication is not planned. Expressive communication is often not conscious at all. However, rhetorical communication is purposeful. When we are using rhetorical communication to influence another person(s), we know that we are trying to influence that person(s).

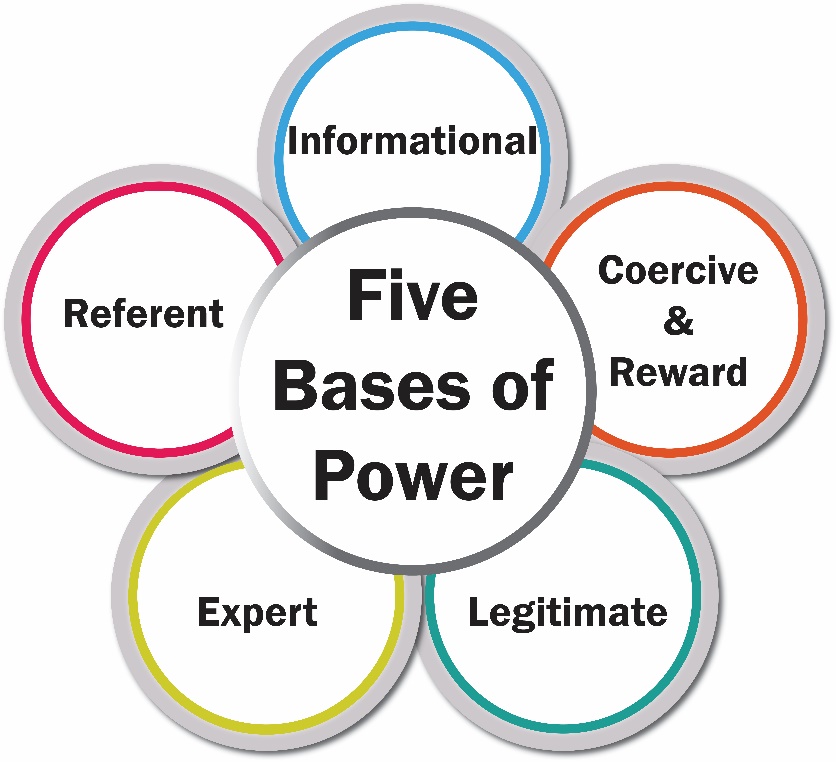

8.2.1 French & Raven’s Five Bases of Power

When we hear the word power, many of us think of superheroes, political leaders, or people in positions of authority. But in the social sciences, power has a specific definition.Power is the degree that a social agent (A) has the ability to get another person(s) (P) to alter their thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors. Unlike influence in general, which can happen unintentionally, power always involves rhetorical communication—it’s deliberate and goal-driven. Power is about intentionally trying to change someone’s mindset or behavior.

French and Raven (1959) identified five bases of power:

- Informational: Informational power refers to a social agent’s ability to bring about a change in thought, feeling, and/or behavior through information. For example, since you initially started school, teachers have had informational power over you. They have provided you with a range of information on history, science, grammar, art, etc. that shape how you think (what constitutes history?), feel (what does it mean to be aesthetically pleasing?), and behave (how do you properly mix chemicals in a lab?). In some ways, informational power is very strong, because it’s often the first form of power with which we come into contact. In fact, when you are taught how to think, feel, and/or behave, this change “now continues without the target necessarily referring to, or even remembering, the [influencer] as being the agent of change” (Raven, 2008).

- Coercive and Reward: Coercive power, is the ability to punish an individual who does not comply with one’s influencing attempts. On the other end of the spectrum, we have reward power (3rd base of power), which is the ability to offer an individual rewards for complying with one’s influencing attempts. We talk about these two bases of power together because they are two sides of the same coin. Furthermore, the same problems with this type of power apply equally to both. Influence can happen if you punish or reward someone; however, as soon as you take away that punishment or reward, the thoughts, feelings, and/or behavior will reverse back to its initial state. Hence, we refer to both coercive and reward power as attempts to get someone to comply with influence, because this is the highest level of influence one can hope to achieve with these two forms of power.

- Legitimate: Legitimate power, is influence that occurs because a person (P) believes that the social agent (A) has a valid right to influence P, and P has an obligation to accept A’s attempt to influence P’s thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors. French and Raven argued that there were two common forms of legitimate power: cultural and structural. Cultural legitimate power occurs when a change agent is viewed as having the right to influence others because of their role in the culture. For example, in some cultures, the elderly may have a stronger right to influence than younger members of that culture. Structural legitimate power, on the other hand, occurs because someone fulfills a specific position within the social hierarchy. For example, your boss may have the legitimate right to influence your thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors in the workplace because they are above you in the organizational hierarchy (French & Raven, 1959).

- Expert: Expert power, is the power we give an individual to influence us because of their perceived knowledge. For example, we often give our physicians the ability to influence our behavior (e.g., eat right, exercise, take medication, etc.) because we view these individuals as having specialized knowledge. However, this type of influence only is effective if P believes A is an expert, P trusts A, and P believes that A is telling the truth. One problem we often face in the 21st Century involves the conceptualization of the word “expert.” Many people in today’s world can be perceived as “experts” just because they write a book, have a talk show, were on a reality TV show, or are seen on news programs (Bauerlein, 2008). Many of these so-called “experts” may have no reasonable skill or knowledge but they can be trumpeted as experts. One of the problems with the Internet is the fundamental flaw that anyone can put information online with only an opinion and no actual facts. Additionally, we often engage in debates about “facts” because we have different talking heads telling us different information. Historically, expert power was always a very strong form of power, but there is growing concern that we are losing expertise and knowledge to unsubstantiated opinions and rumor mongering.

- Referent: Referent power, is a social agent’s ability to influence another person because P wants to be associated with A. Ultimately, referent power is about relationship building and the desire for a relationship. If A is a person P finds attractive, then P will do whatever they need to do to become associated with A. If A belongs to a group, then P will want to join that group. Ultimately, this relationship exists because P wants to think, feel, and behave as A does. For example, if A decides that he likes modern art, then P will also decide to like modern art. If A has a very strong work ethic in the workplace, then P will adopt a strong work ethic in the workplace as well. Often A has no idea of the influence they are having over P. Ultimately, the stronger P desires to be associated with A, the more referent power A has over P.

8.2.2 Power and Interpersonal Conflict

Power is not only central to our ability to influence others—it is also a key factor in how interpersonal conflicts emerge, escalate, and are resolved. Every relationship involves a dynamic balance of power, whether that balance is equal or unequal. When one person attempts to assert influence and the other resists, a power struggle can occur, which often lies at the heart of many interpersonal conflicts.

In fact, many conflicts are not just about surface-level issues like chores, plans, or preferences, but about deeper questions of control, autonomy, and perceived fairness. Who gets to make the final decision? Whose needs or goals take priority? Who holds the legitimate right to assert influence? These are all questions rooted in the distribution and perception of power in a relationship.

The bases of power discussed earlier—especially coercive, reward, and legitimate power—can often exacerbate conflict if they are perceived as unfair or misused. For example, if one person uses coercive power to dominate a conversation or force a decision, the other may feel resentful, powerless, or disrespected. Conversely, power rooted in expertise, information, or referent influence can sometimes help de-escalate conflict, particularly when it is used to build trust, offer perspective, or reinforce mutual respect.

Understanding how power operates in interpersonal relationships allows us to better navigate conflict. Effective conflict management often involves recognizing imbalances of power, being mindful of how we use our own influence, and working toward communication strategies that empower all parties involved.

As we transition to discussing interpersonal conflict in more detail, keep in mind how power shapes not only what conflicts arise, but how they are handled—and whether they are resolved constructively or destructively.

8.3 Emotions and Feelings

While power dynamics shape who holds influence in interpersonal conflict, emotions and feelings often dictate how that conflict unfolds. Regardless of one’s position or power, human beings bring emotional responses into every interaction. These emotions can either escalate tensions or help de-escalate situations—depending on how they are recognized and managed. Understanding our emotional responses, and those of others, is key to resolving conflicts constructively.

Emotions and feelings play a significant role in shaping how interpersonal conflicts unfold and are managed. When individuals experience strong emotions, such as anger, frustration, or hurt, they may react impulsively, escalating the conflict or making it harder to find common ground. Additionally, emotions can cloud judgment, leading to misinterpretations of others’ intentions and heightened defensiveness. On the other hand, being aware of and managing emotions can help individuals approach conflict with greater empathy, patience, and clarity, enabling more productive and respectful communication.

As we discuss the effects of our emotions and feelings on conflicts, it’s important to differentiate between emotions and feelings. Emotions are our reactions to stimuli in the outside environment. Emotions, therefore, can be objectively measured by blood flow, brain activity, and nonverbal reactions to things. Feelings, on the other hand, are the responses to thoughts and interpretations given to emotions based on experiences, memory, expectations, and personality. So, there is an inherent relationship between emotions and feelings, but we do differentiate between them. Table 8.1 breaks down the differences between the two concepts.

Table 8.1 The Differences of Emotions and Feelings

| © John W. Voris, CEO of Authentic Systems, www.authentic-systems.com Reprinted here with permission. |

|

| Feelings: | Emotions: |

|---|---|

| Feelings tell us “how to live.” | Emotions tell us what we “like” and “dislike.” |

| Feelings state: “There is a right and wrong way to be.“ | Emotions state: “There are good and bad actions.” |

| Feelings state: “your emotions matter.” | Emotions state: “The external world matters.” |

| Feelings establish our long-term attitude toward reality. | Emotions establish our initial attitude toward reality. |

| Feelings alert us to anticipated dangers and prepares us for action. | Emotions alert us to immediate dangers and prepare us for action. |

| Feelings ensure long-term survival of self (body and mind). | Emotions ensure immediate survival of self (body and mind). |

| Feelings are Low-key but Sustainable. | Emotions are Intense but Temporary. |

| Happiness: is a feeling. | Joy: is an emotion. |

| Worry: is a feeling. | Fear: is an emotion. |

| Contentment: is a feeling. | Enthusiasm: is an emotion. |

| Bitterness: is a feeling. | Anger: is an emotion. |

| Love: is a feeling. | Lust: is an emotion. |

| Depression: is a feeling. | Sadness: is an emotion. |

It’s important to understand that we are all allowed to be emotional beings. Being emotional is an inherent part of being a human. For this reason, it’s important to avoid phrases like “don’t feel that way” or “they have no right to feel that way.” Again, our emotions are our emotions, and, when we negate someone else’s emotions, we are negating that person as an individual and taking away their right to emotional responses.

We all have the ability to alter our emotions. Altering our emotional states (in a proactive way) is how we get through life. Maybe you just broke up with someone, and listening to music helps you work through the grief you are experiencing to get to a better place. For others, they need to openly communicate about how they are feeling in an effort to process and work through emotions. The worst thing a person can do is attempt to deny that the emotion exists.

- Think of this like a balloon. With each breath of air you blow into the balloon, you are bottling up more and more emotions. Eventually, that balloon will get to a point where it cannot handle any more air in it before it explodes. Humans can be the same way with emotions when we bottle them up inside. The final breath of air in our emotional balloon doesn’t have to be big or intense. However, it can still cause tremendous emotional outpouring that is often very damaging to the person and their interpersonal relationships with others.

Research has demonstrated that how we handle our negative emotions during conflicts can affect the rate of de-escalations and mediation (Bloch, Haase, & Levenson, 2014).

8.3.1 Emotions and Conflict

Emotions are at the heart of most interpersonal conflicts. Whether a disagreement stems from unmet expectations, a perceived slight, or clashing values, emotions serve as both the fuel and the signal for conflict. They alert us that something important is at stake, and they influence how we choose to respond. However, while emotions may be automatic and instinctual (Levenson, 1994), how we handle them is a choice—and that choice directly impacts the course and outcome of the conflict.

Strong emotions such as anger, jealousy, fear, or resentment can intensify conflict when left unexamined or unmanaged. For example, anger may provoke shouting or passive-aggressive behavior, while fear may cause someone to withdraw or avoid the issue altogether. When emotions take control of our actions, we often lose the ability to listen, empathize, or reason through the problem—leading to miscommunication, blame, and escalation.

Conversely, recognizing and validating emotions—both our own and others’—can be a powerful tool for de-escalating tension and building understanding (Ekman, 2003). Emotional awareness enables us to take a pause, reflect on what we are feeling, and ask what unmet need lies underneath that emotion. For instance, frustration in a conflict might signal a need for autonomy, respect, or clarity. When we focus on articulating those needs instead of attacking the other person, we create space for collaboration instead of combat.

This connection between emotion and conflict is central to the idea of emotional intelligence (EQ). Emotional intelligence(EQ) is an individual’s appraisal and expression of their emotions and the emotions of others in a manner that enhances thought, living, and communicative interactions. Furthermore, we learned that EQ is built by four distinct emotional processes: perceiving, understanding, managing, and using emotions (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). Take a minute and complete Table 8.2, which is a simple 20-item questionnaire designed to help you evaluate your own EQ.

Table 8.2 Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire

Read the following questions and select the answer that corresponds with your perception. Do not be concerned if some of the items appear similar. Please use the scale below to rate the degree to which each statement applies to you.

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

_____1. I am aware of my emotions as I experience them.

_____2. I easily recognize my emotions.

_____3. I can tell how others are feeling simply by watching their body movements.

_____4. I can tell how others are feeling by listening to their voices.

_____5. When I look at people’s faces, I generally know how they are feeling.

_____6. When my emotions change, I know why.

_____7. I understand that my emotional state is rarely comprised of one single emotion.

_____8. When I am experiencing an emotion, I have no problem easily labeling that emotion.

_____9. It’s completely possible to experience two opposite emotions at the same time (e.g., love & hate; awe & fear; joy & sadness, etc.).

_____10. I can generally tell when my emotional state is shifting from one emotion to another.

_____11. I don’t let my emotions get the best of me.

_____12. I have control over my own emotions.

_____13. I can analyze my emotions and determine if they are reasonable or not.

_____14. I can engage or detach from an emotion depending on whether I find it informative or useful.

_____15. When I’m feeling sad, I know how to seek out activities that will make me happy.

_____16. I can create situations that will cause others to experience specific emotions.

_____17. I can use my understanding of emotions to have more productive interactions with others.

_____18. I know how to make other people happy or sad.

_____19. I often lift people’s spirits when they are feeling down.

_____20. I know how to generate negative emotions and enhance pleasant ones in my interactions with others.

Scoring:

| Perceiving Emotions | Add scores for items 1, 2, 3, 4, & 5 | = | ||

| Understanding Emotions | Add scores for items 6, 7, 8, 9, & 10 | = | ||

| Managing Emotions | Add scores for items 11, 12, 13, 14, & 15 | = | ||

| Using Emotions | Add scores for items 16, 17, 18, 19, & 20 | = |

Interpreting Your Scores:

Each of the four parts of the EQ Model can have a range of 5 to 25. Scores under 11 represent low levels of EQ for each aspect. Scores between 12 and 18 represent average levels of EQ. Scores 19 and higher represent high levels of EQ.

Emotional intelligence plays a crucial role in effectively handling conflict, as it involves the ability to recognize, understand, and manage both your own emotions and those of others. Individuals with high emotional intelligence are better equipped to navigate the emotional landscape of conflict, allowing them to remain calm, empathetic, and thoughtful in tense situations. They can identify underlying emotions that fuel disagreements, such as frustration, fear, or hurt, and respond in ways that de-escalate tension rather than inflame it. Emotional intelligence also helps people communicate more clearly and compassionately, fostering open dialogue and mutual understanding. By managing emotions constructively, individuals are more likely to resolve conflicts in ways that strengthen relationships, build trust, and promote long-term collaboration. Ultimately, emotional intelligence allows people to approach conflict not as a threat, but as an opportunity for growth and deeper connection.

Ultimately, conflicts are less about removing emotions and more about managing them. Moreover, not all emotions in conflict are negative. Emotions such as concern, hope, or care can drive individuals to initiate difficult conversations in the interest of preserving or strengthening a relationship. In this way, emotions can serve as guides—not just warning signals, but also motivators to engage and repair. By developing emotional literacy—the ability to identify what we feel, why we feel it, and how it affects others—we can engage in more constructive, respectful, and honest communication.

8.3.2 Expressing Feelings in Conflict

Developing emotional intelligence lays the groundwork for more mindful and constructive communication during conflict—but recognizing our emotions is only the first step. The next challenge is how we express those emotions. Often, conflict escalates not because of what we feel, but how we communicate those feelings. When our emotions are filtered through blame, criticism, or defensiveness, the chances of resolution shrink. This brings us to the importance of expression—how we give voice to our feelings and unmet needs in ways that invite understanding rather than push others away.

According to Marshall Rosenberg, the creator of nonviolent communication, “You” statements often reflect moralistic judgments where we imply that the other person is wrong or bad based on their behavior (2003). These judgments shift blame and deny responsibility for our own thoughts, feelings, and actions. It’s important to remember that no one can make us feel a certain way—we choose our emotional responses. When we blame others for our feelings, we trigger defensiveness and escalate conflict, making it harder to get our needs met in the relationship.

Behind every negative emotion lies an unmet need. Blaming others doesn’t resolve the core issue—it often intensifies disconnection. For example, someone might say, “If you go hang out with your friends tonight, I’ll hurt myself, and it will be your fault.” In this case, the speaker uses blame to manipulate their partner’s behavior rather than expressing vulnerability or needs. This kind of communication creates unhealthy dynamics where neither person’s needs are clearly acknowledged or met.

However, expressing emotions is just the first step. Effective communication also requires identifying the underlying need behind the feeling. These needs are not limited to basic survival needs from Maslow’s Hierarchy, but also include emotional and relational needs—such as autonomy, connection, or respect (adapted from Rosenberg, 2003). When these needs go unmet, we often act out emotionally in an attempt to be heard or understood.

A more constructive response might be: “I feel hurt when you yell at me because I need to feel respected.” This statement shares an emotion and connects it to a need—without judgment or blame.

Notice that this kind of language avoids labeling the other person as wrong. Instead, it focuses on one’s own internal experience, inviting understanding rather than defensiveness.

Table 8.3 Underlying Human Needs

| Area | Need |

|---|---|

| Autonomy | to choose one’s dreams, goals, values |

| to choose one’s plan for fulfilling one’s dreams, goals, values | |

| Spiritual Communion | beauty, harmony |

| inspiration | |

| order, peace | |

| Physical Nurturance | air |

| food, water | |

| movement, exercise | |

| protection from life-threatening forms of life: viruses, bacteria, insects, predatory animals | |

| rest | |

| shelter | |

| Integrity | authenticity |

| creativity | |

| meaning, self-worth | |

| Interdependence | acceptance, understanding, empathy |

| appreciation, consideration | |

| closeness, love, community, warmth | |

| reassurance | |

| respect, trust, honesty | |

| Source: Adapted from Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life 2nd Ed by Dr. Marshall B. Rosenberg, 2003–published by PuddleDancer Press and Used with Permission. For more information visit www.CNVC.org and www.NonviolentCommunication.com |

|

Next, let’s discuss common communication strategies for managing conflict.

8.4 Conflict Management Strategies

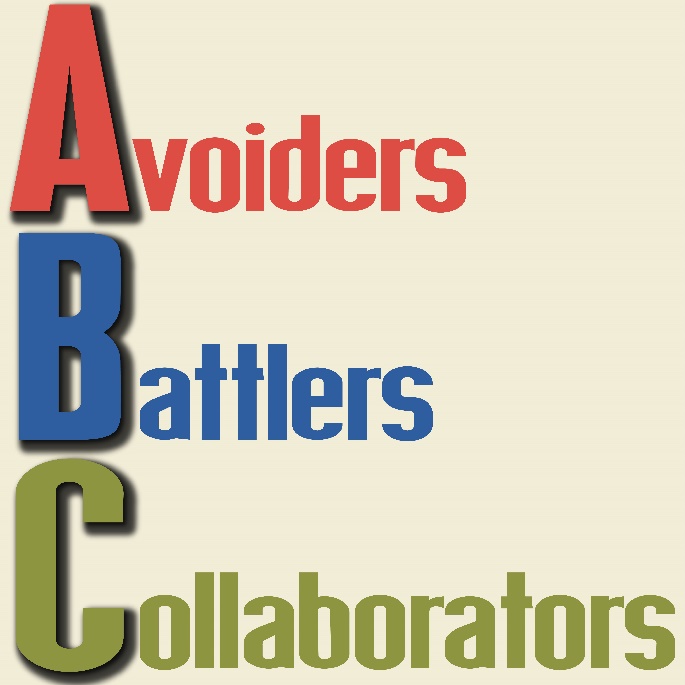

Many researchers have attempted to understand how humans handle conflict with one another. You may see classifications of conflict based on whether participants are Integrative or distributive ; and how assertive and cooperative they are. All of these approaches are valid to understanding conflict. However, in this textbook we have chosen to simplify conflict management into 3 primary strategies known as the ABCs.

8.4.1 ABC’s of Conflict

So how do you typically approach a conflict situation? Go ahead and take a moment to complete the questionnaire in Table 8.4 to identify some of your own common patterns.

Table 8.4 ABC’s of Conflict Management

Instructions: Read the following questions and select the answer that corresponds with how you typically behave when engaged in conflict with another person. Do not be concerned if some of the items appear similar. Please use the scale below to rate the degree to which each statement applies to you.

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

When I start to engage in a conflict, I _______________

_____1. Keep the conflict to myself to avoid rocking the boat.

_____2. Do my best to win.

_____3. Try to find a solution that works for everyone.

_____4. Do my best to stay away from disagreements that arise.

_____5. Create a strategy to ensure my successful outcome.

_____6. Try to find a solution that is beneficial for those involved.

_____7. Avoid the individual with whom I’m having the conflict.

_____8. Won’t back down unless I get what I want.

_____9. Collaborate with others to find an outcome OK for everyone.

_____10. Leave the room to avoid dealing with the issue.

_____11. Take no prisoners.

_____12. Find solutions that satisfy everyone’s expectations.

_____13. Shut down and shut up in order to get it over with as quickly as possible.

_____14. See it as an opportunity to get what I want.

_____15. Try to integrate everyone’s ideas to come up with the best solution for everyone.

_____16. Keep my disagreements to myself.

_____17. Don’t let up until I win.

_____18. Openly raise everyone’s concerns to ensure the best outcome possible.

Scoring:

Avoiders

Add Items 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16______

Battlers

Add Items 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17______

Collaborators

Add Items 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18______

Interpretation: Scores for each subscale should range from 6 to 30. Scores under 14 are considered low, scores 15 to 23 are considered moderate, and scores over 24 are considered high.

Avoiders

Conflict avoidance is the practice of deliberately steering clear of addressing disagreements or confrontations in personal or professional relationships. People often avoid conflict because they fear negative outcomes, such as damaged relationships, emotional discomfort, or escalated tension. Some individuals may also avoid conflict due to a desire to maintain harmony, low self-confidence, or previous experiences where conflict led to undesirable consequences. While conflict avoidance can offer short-term benefits, like reducing immediate stress or preserving peace, it has significant drawbacks. On the positive side, avoiding conflict can sometimes prevent unnecessary arguments or allow time for emotions to cool down. However, consistently avoiding conflict often leads to unresolved issues, increased frustration, and weakened relationships over time. When people avoid addressing problems, underlying tensions may fester, leading to larger, more difficult conflicts in the future. Ultimately, while avoidance might seem easier in the moment, it can prevent open communication and inhibit healthy problem-solving.

Table 8.5 provides a list of common tactics used by avoiders in conflict (Sillars, Coletti, Parry, & Rogers, 1982).

Table 8.5 Avoidant Conflict Management Strategies

| Conflict Management Tactic | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Simple Denial | Statements that deny the conflict. | “No, I’m perfectly fine.” |

| Extended Denial | Statements that deny conflict with a short justification. | “No, I’m perfectly fine. I just had a long night.” |

| Underresponsiveness | Statements that deny the conflict and then pose a question to the conflict partner. | “I don’t know why you are upset, did you wake up on the wrong side of the bed this morning?” |

| Topic Shifting | Statements that shift the interaction away from the conflict. | “Sorry to hear that. Did you hear about the mall opening?” |

| Topic Avoidance | Statements designed to clearly stop the conflict. | “I don’t want to deal with this right now.” |

| Abstractness | Statements designed to shift a conflict from concrete factors to more abstract ones. | “Yes, I know I’m late. But what is time really except a construction of humans to force conformity.” |

| Semantic Focus | Statements focused on the denotative and connotative definitions of words. | “So, what do you mean by the word ‘sex’?” |

| Process Focus | Statements focused on the “appropriate” procedures for handling conflict. | “I refuse to talk to you when you are angry.” |

| Joking | Humorous statements designed to derail conflict. | “That’s about as useless as a football bat.” |

| Ambivalence | Statements designed to indicate a lack of caring. | “Whatever!” “Just do what you want.” |

| Pessimism | Statements that devalue the purpose of conflict. | “What’s the point of fighting over this? Neither of us are changing our minds.” |

| Evasion | Statements designed to shift the focus of the conflict. | “I hear the Joneses down the street have that problem, not us.” |

| Stalling | Statements designed to shift the conflict to another time. | “I don’t have time to talk about this right now.” |

| Irrelevant Remark | Statements that have nothing to do with the conflict. | “I never knew the wallpaper in here had flowers on it.” |

Battlers

“Battlers,” also known as aggressive or competitive communicators, approach conflict with a win-at-all-costs mindset, viewing disagreements as a zero-sum game where one side emerges victorious while the other loses. Battlers engage in what is called distributive conflict, where their primary focus is on achieving their own goals, often without regard to the feelings or needs of others. This approach to conflict can be highly antagonistic and personalistic, as battlers tend to target the individual rather than just the issue at hand. While this style can sometimes lead to short-term wins or assertively defending one’s position, it often causes significant relational damage, fostering resentment and hostility. The aggressive nature of battlers may lead to burned bridges and strained communication in the long run. On the positive side, battlers can be decisive, willing to take charge and tackle difficult situations head-on. However, the downside is that their lack of concern for collaboration or compromise can result in broken trust, weakened relationships, and an inability to resolve conflicts in a way that benefits both parties (Sillars et al., 1982).

Table 8.6 provides a list of common tactics used by battlers in conflict (Sillars et al., 1982).

Table 8.6 Battling Conflict Management Strategies

| Conflict Management Tactic | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Faulting | Statements that verbally criticize a partner. | “Wow, I can’t believe you are so dense at times.” |

| Rejection | Statements that express antagonistic disagreement. | “That is such a dumb idea.” |

| Hostile Questioning | Questions designed to fault a partner. | “Who died and made you king?” |

| Hostile Joking | Humorous statements designed to attack a partner. | “I do believe a village has lost its idiot.” |

| Presumptive Attribution | Statements designed to point the meaning or origin of the conflict to another source. | “You just think that because your father keeps telling you that.” |

| Avoiding Responsibility | Statements that deny fault. | “Not my fault, not my problem.” |

| Prescription | Statements that describe a specific change to another’s behavior. | “You know, if you’d just stop yelling, maybe people would take you seriously.” |

| Threat | Statements designed to inform a partner of a future punishment. | “You either tell your mother we’re not coming, or I’m getting a divorce attorney.” |

| Blame | Statements that lay culpability for a problem on a partner. | “It’s your fault we got ourselves in this mess in the first place.” |

| Shouting | Statements delivered in a manner with an increased volume. | “DAMMIT! GET YOUR ACT TOGETHER!” |

| Sarcasm | Statements involving the use of irony to convey contempt, mock, insult, or wound another person. | “The trouble with you is that you lack the power of conversation but not the power of speech.” |

Collaborators

Collaborators approach conflict with a focus on finding mutually beneficial solutions, aiming for outcomes where both sides feel satisfied with the resolution. They engage in prosocial communication behaviors, emphasizing open dialogue, active listening, and problem-solving to ensure that all parties’ needs are considered. Collaborators may either work toward a fully cooperative solution or, when necessary, compromise, understanding that each side may need to give up something to reach a fair and balanced outcome. While this approach is often ideal, it can be difficult to achieve, especially when one party is unwilling to collaborate or is more focused on “winning” the conflict. In such cases, collaborative strategies may not be effective because successful collaboration requires both parties to engage in good faith. Despite these challenges, collaboration is typically seen as a constructive approach to conflict, as it strengthens relationships, builds trust, and encourages long-term cooperation by valuing the perspectives and needs of everyone involved.

Table 8.7 provides a list of common tactics used by collaborators in conflict (Sillars et al., 1982).

Table 8.7 Collaborative Conflict Management Strategies

| Conflict Management Tactic | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptive Acts | Statements that describe obvious events or factors. | “Last time your sister babysat our kids, she yelled at them.” |

| Qualification | Statements that explicitly explain the conflict. | “I am upset because you didn’t come home last night.” |

| Disclosure | Statements that disclose one’s thoughts and feelings in a non-judgmental way. | “I get really worried when you don’t call and let me know where you are.” |

| Soliciting Disclosure | Questions that ask another person to disclose their thoughts and feelings. | “How do you feel about what I just said?” |

| Negative Inquiry | Statements allowing for the other person to identify your negative behaviors. | “What is it that I do that makes you yell at me?” |

| Empathy | Statements that indicate you understand and relate to the other person’s emotions and experiences. | “I know this isn’t easy for you.” |

| Emphasize Commonalities | Statements that highlight shared goals, aims, and values. | “We both want what’s best for our son.” |

| Accepting Responsibility | Statements acknowledging the part you play within a conflict. | “You’re right. I sometimes let my anger get the best of me.” |

| Initiating Problem-Solving | Statements designed to help the conflict come to a mutually agreed upon solution. | “So let’s brainstorm some ways that will help us solve this.” |

| Concession | Statements designed to give in or yield to a partner’s goals, aims, or values. | “I promise, I will make sure my homework is complete before I watch television.” |

Before we conclude this section, we do want to point out that conflict management strategies are often reciprocated by others. If you start a conflict in a highly competitive way, do not be surprised when your conflicting partner mirrors you and starts using distributive conflict management strategies in return. The same is also true for integrative conflict management strategies. When you start using integrative conflict management strategies, you may be able to deescalate a problematic conflict by using integrative conflict management strategies.

8.5 Resolving Conflict Effectively

Cahn and Abigail created a very simple model that can help us to think through a heated conflict situation (2014). They called the model the STLC Conflict Model because it stands for stop, think, listen, and then communicate.

Step 1: Stop

The first thing an individual needs to do when interacting with another person during conflict is to take the time to be present within the conflict itself. Too often, people engaged in a conflict say whatever enters their mind before they’ve really had a chance to process the message and think of the best strategies to use to send that message. Others end up talking past one another during a conflict because they simply are not paying attention to each other and the competing needs within the conflict. Communication problems often occur during conflict because people tend to react to conflict situations when they arise instead of being mindful and present during the conflict itself. For this reason, it’s always important to take a breath during a conflict and first stop.

Sometimes these “time outs” need to be physical. Maybe you need to leave the room and go for a brief walk to calm down, or maybe you just need to get a glass of water. Whatever you need to do, it’s important to take this break. This break takes you out of a “reactive stance into a proactive one” (Cahn & Abigail, 2014).

Step 2: Think

Once you’ve stopped, you now have the ability to really think about what you are communicating. You want to think through the conflict itself. What is the conflict really about? Often people engage in conflicts about superficial items when there are truly much deeper issues that are being avoided. You also want to consider what possible causes led to the conflict and what possible courses of action you think are possible to conclude the conflict. Cahn and Abigail argue that there are four possible outcomes that can occur: do nothing, change yourself, change the other person, or change the situation.

- First, you can simply sit back and avoid the conflict. Maybe you’re engaging in a conflict about politics with a family member, and this conflict is actually just going to make everyone mad. For this reason, you opt just to stop the conflict and change topics to avoid making people upset. One of our coauthors was at a funeral when an uncle asked our coauthor about our coauthor’s impression of the current President. Our coauthor’s immediate response was, “Do you really want me to answer that question?” Our coauthor knew that everyone else in the room would completely disagree, so our coauthor knew this was probably a can of worms that just didn’t need to be opened.

- Second, we can change ourselves. Often, we are at fault and start conflicts. We may not even realize how our behavior caused the conflict until we take a step back and really analyze what is happening. When it comes to being at fault, it’s very important to admit that you’ve done wrong. Nothing is worse (and can stoke a conflict more) than when someone refuses to see their part in the conflict.

- Third, we can attempt to change the other person. Let’s face it, changing someone else is easier said than done. Just ask your parents/guardians! All of our parents/guardians have attempted to change our behaviors at one point or another, and changing people is very hard. Even with the powers of punishment and reward, a lot of time change only lasts as long as the punishment or the reward. One of our coauthors was in a constant battle with our coauthors’ parents about thumb sucking as a child. Our coauthor’s parents tried everything to get the thumb sucking to stop. They finally came up with an ingenious plan. They agreed to buy a toy electric saw if their child didn’t engage in thumb sucking for the entire month. Well, for a whole month, no thumb sucking occurred at all. The child got the toy saw, and immediately inserted the thumb back into our coauthor’s mouth. This short story is a great illustration of the problems that can be posed by rewards. Punishment works the same way. As long as people are being punished, they will behave in a specific way. If that punishment is ever taken away, so will the behavior.

- Lastly, we can just change the situation. Having a conflict with your roommates? Move out. Having a conflict with your boss? Find a new job. Having a conflict with a professor? Drop the course. Admittedly, changing the situation is not necessarily the first choice people should take when thinking about possibilities, but often it’s the best decision for long-term happiness. In essence, some conflicts will not be settled between people. When these conflicts arise, you can try and change yourself, hope the other person will change (they probably won’t, though), or just get out of it altogether.

Step 3: Listen

The third step in the STLC model is listen. Humans are not always the best listeners. As we discussed in Chapter 6, active listening is a skill that requires us to pay attention, reflect, and respond to a partner. Unfortunately, during a conflict situation, this is a skill that is desperately needed and often forgotten. When we feel defensive during a conflict, our listening becomes spotty at best because we start to focus on ourselves and protecting ourselves instead of trying to be empathic and seeing the conflict through the other person’s eyes.

One mistake some people make is to think they’re listening, but in reality, they’re listening for flaws in the other person’s argument (known as defensive listening). We often use this type of selective listening as a way to devalue the other person’s stance. In essence, we will hear one small flaw with what the other person is saying and then use that flaw to demonstrate that obviously everything else must be wrong as well.

The goal of listening must be to suspend your judgment and really attempt to be present enough to accurately interpret the message being sent by the other person. When we listen in this highly empathic way, we are often able to see things from the other person’s point-of-view, which could help us come to a better-negotiated outcome in the long run.

Step 4: Communicate

Lastly, but certainly not least, we communicate with the other person. Notice that Cahn and Abigail (2014) put communication as the last part of the STLC model because it’s the hardest one to do effectively during a conflict if the first three are not done correctly. When we communicate during a conflict, we must be hyper-aware of our nonverbal behavior (eye movement, gestures, posture, etc.). Nothing will kill a message faster than when it’s accompanied by bad nonverbal behavior. For example, rolling one’s eyes while another person is speaking is not an effective way to engage in conflict. One of our coauthors used to work with two women who clearly despised one another. They would never openly say something negative about the other person publicly, but in meetings, one would roll her eyes and make these non-word sounds of disagreement. The other one would just smile, slow her speech, and look in the other woman’s direction. Everyone around the conference table knew exactly what was transpiring, yet no words needed to be uttered at all.

During a conflict, it’s important to be assertive and stand up for your ideas without becoming verbally aggressive. Conversely, you have to be open to someone else’s use of assertiveness as well without having to tolerate verbal aggression. We often end up using mediators to help call people on the carpet when they communicate in a fashion that is verbally aggressive or does not further the conflict itself. As Cahn and Abigail (2014) note, “People who are assertive with one another have the greatest chance of achieving mutual satisfaction and growth in their relationship.”

Assertive Communication: Respecting Yourself and Others

Assertive communication is a key skill for expressing emotions, setting boundaries, and advocating for your needs in a healthy, respectful way. According to Beebe, Beebe, and Redmond (2020), assertive communication means being “able to pursue one’s own best interests without denying a person’s rights” (p. 173). Unlike aggressive communication (which violates others’ boundaries) or passive communication (which ignores your own needs), assertive communication is rooted in mutual respect.

Practicing assertive communication helps you express your thoughts and feelings honestly while also considering the perspective and dignity of others. It’s a valuable tool for maintaining relationships, resolving conflict, and navigating emotional situations effectively.

Here is a five-step model to guide assertive communication:

1. Describe the situation or behavior

Start by objectively stating what happened—without blame, judgment, or exaggeration. Focus on observable behavior, not assumptions or interpretations.

Example: “When you interrupted me during the meeting…”

2. Disclose your feelings

Share your genuine emotional response using “I” statements. This keeps the focus on your experience rather than accusing the other person.

“…I felt frustrated and dismissed…”

3. Identify the effects

Explain why the behavior or situation matters by highlighting the impact it had on you or others.

“…because I had prepared my part and was hoping to contribute to the discussion.”

4. Listen to the other person’s perspective

Assertiveness is not a one-way street. After expressing yourself, give the other person a chance to respond. Stay open and attentive, even if their perspective is different from your own.

“Can you help me understand what was going on from your end?”

5. Paraphrase to clarify understanding

Paraphrasing shows that you’re actively listening and trying to understand the other person. It also helps prevent miscommunication.

“So you were feeling rushed to finish and didn’t realize I hadn’t spoken yet—is that right?”

Assertive communication doesn’t guarantee you’ll get exactly what you want, but it does set the stage for healthy dialogue and problem-solving. By clearly stating your needs and being open to others, you foster trust and mutual respect in relationships. It’s a powerful way to advocate for yourself—without stepping on anyone else’s rights.

Wrap Up

Conflict is an inevitable part of all human relationships. Throughout this chapter, we examined the sources of conflict, common styles of conflict management, and communication strategies that can help us navigate disagreements more constructively. While conflict may feel uncomfortable in the moment, unmanaged or poorly handled conflict can do lasting harm. On the other hand, skillful conflict management builds trust, deepens connection, and promotes mutual respect.

The key takeaway is that managing conflict effectively is not about avoiding it or “winning” an argument—it’s about using thoughtful, respectful communication to find understanding and resolution. Whether in personal relationships, friendships, or professional settings, the ability to approach conflict with empathy, active listening, and a willingness to collaborate is one of the most powerful communication skills we can develop.

References

Beebe, S. A., Beebe, S. J., & Redmond, M. V. (2020). Interpersonal Communication: Relating to Others. Pearson.

Bloch, L., Haase, C. M., & Levenson, R. W. (2014). Emotion regulation predicts marital satisfaction: More than a wives’ tale. Emotion, 14(1), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034272

Cahn D. D., & Abigail, R. A. (2014). Managing conflict through communication (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

Ekman, P. (2003). Emotions revealed: Recognizing faces and feelings to improve communication and emotional life. Henry Holt & Co.

French, J. R. P., Jr., & Raven, B. H. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 150–167). Institute for Social Research.

Levenson, R. W. (1994). Human emotion: A functional view. In P. Ekman and R. J. Davidson (Eds.), The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions (pp. 123-126). Oxford University Press.

McCroskey, J. C., & Wheeless, L. R. (1976). An introduction to human communication. Allyn & Bacon.

Raven, B. H. (2008). The bases of power and the power/interaction model of interpersonal influence. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 8, 1-22.

Rosenberg, M. B. (2003). Nonviolent communication: A language of life (2nd ed.). Puddle Dancer Press.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality, 9, 185-211.

Sillars, A. L., Coletti, S., Parry, D., & Rogers, M. (1982). Coding verbal conflict tactics: Nonverbal and perceptual correlates of the ‘avoidance-competitive-cooperative’ distinction. Human Communication Research, 9(1), 83-95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1982.tb00685.x

Simons, H. W. (1972). Persuasion in social conflicts: A critique of prevailing conceptions and a framework for future research. Speech Monographs, 39(4), 227–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637757209375763

Wrench, J. S., McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (2008). Human communication in everyday life: Explanations and applications. Allyn & Bacon.

Yellowstone National Park Staff. (2015, February 15). Why do geysers erupt? Retrieved from: https://www.yellowstonepark.com/things-to-do/geysers-erupt

Figures.

Figure 8.1 : Krukau, Y. (2021). People having conflict while working. Pexels license. Retrieved from https://www.pexels.com/photo/people-having-conflict-while-working-7640830/.

Figure 8.2 French & Raven’s Five Bases of Power. Interpersonal Communication Copyright © by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt.

Figure 8.3 Conflict Management Styles. Interpersonal Communication Copyright © by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt.

Figure 8.4 Avoiders. Upset young Indian couple after conflict. Ketut Subiyanto. 2020. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.5 Battlers. Man and Woman wearing brown leather jackets. Vera Arsic. 2018. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.6 Collaborate. Photo of women talking while sitting. Fauxels. 2019. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.7 STLC Conflict Model. Interpersonal Communication Copyright © by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt.

Figure 8.8 Hurley, C. M. (2025). The five steps of assertive communication.

This chapter was adapted from Conflict in Relationships in Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench, Narissa M. Punyanunt-Carter, and Katerina S. Thweatt, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 license. It has been modified and expanded by the Editor to fit the context of Communication in the Real World, and is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

An interactive process occurring when conscious beings (individuals or groups) have opposing or incompatible actions, beliefs, goals, ideas, motives, needs, objectives, obligations, resources, and/or values.

When individuals involved in a relationship characterize it as continuous and important.

Purposefully creating and sending messages to another person in the hopes of altering another person’s thinking, feelings, and/or behaviors.

The degree that a social agent (A) has the ability to get another person(s) (P) to alter their thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors.

A social agent’s ability to bring about a change in thought, feeling, and/or behavior through information.

The ability to punish an individual who does not comply with one’s influencing attempts.

The ability to offer an individual rewards for complying with one’s influencing attempts.

Influence that occurs because a person (P) believes that the social agent (A) has a valid right (generally based on cultural or hierarchical standing) to influence P, and P has an obligation to accept A’s attempt to influence P’s thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors.

The ability of an individual to influence another because of their level of perceived knowledge or skill.

A social agent’s (A) ability to influence another person (P) because P wants to be associated with A.

The physical reactions to stimuli in the outside environment.

The responses to thoughts and interpretations given to emotions based on experiences, memory, expectations, and personality.

An individual’s appraisal and expression of their emotions and the emotions of others in a manner that enhances thought, living, and communicative interactions.

A win-win approach to conflict, whereby both parties attempt to come to a settled agreement that is mutually beneficial.

A win-lose approach, whereby conflicting parties see their job as to win and make sure the other person or group loses.

able to pursue one’s own best interests without denying a person’s rights